Reverend Richard Warner's 'A Walk through Wales': the Buckley bit, containing a description of pottery making and mentioning the smelt"

Buckley

September 1798

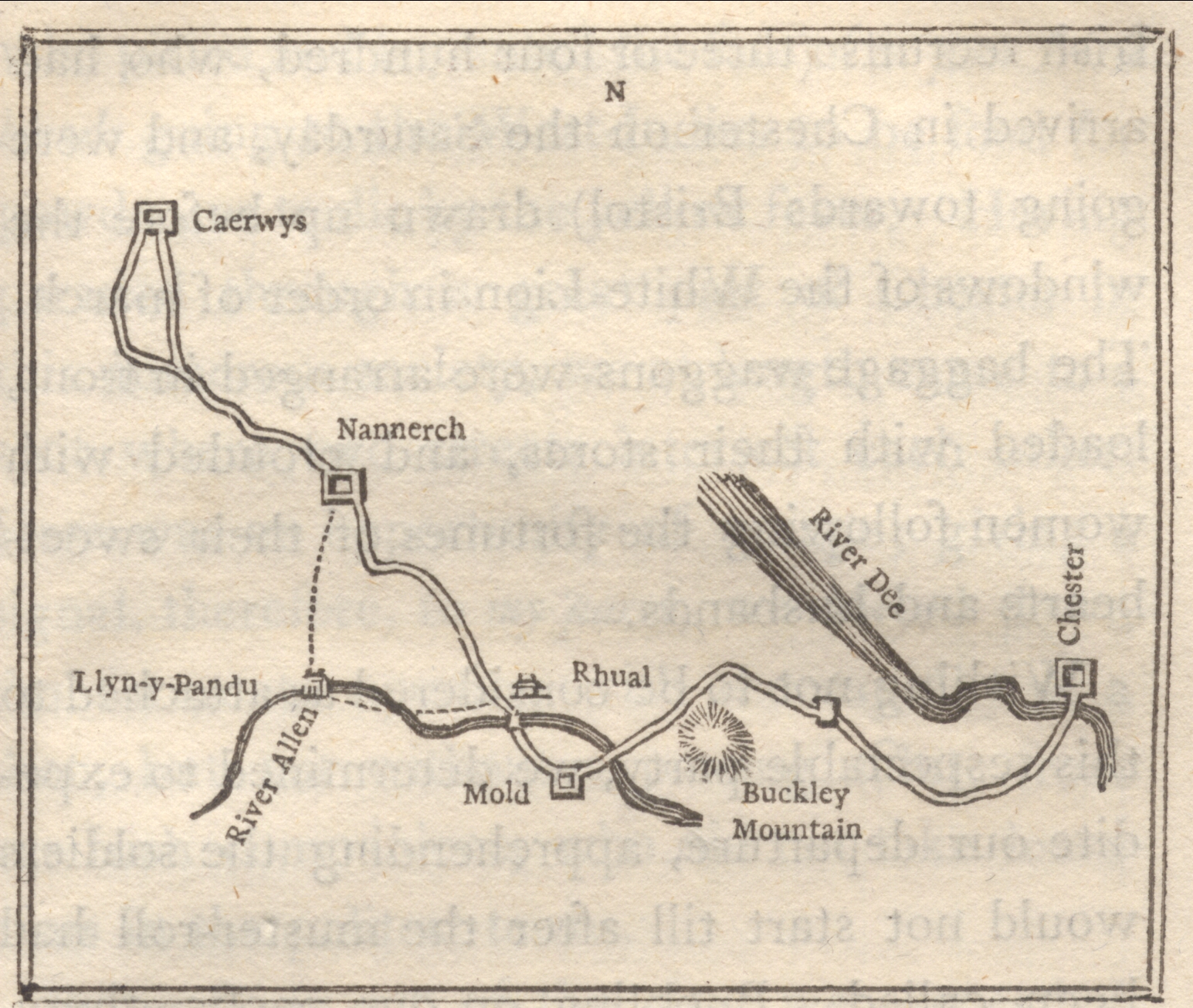

See 96.75 for more information. The Buckley section is highlighted.

********************

LETTER X.

TO THE SAME.

Caerwys, Aug. 27th.

Our departure from Chester this morning was attended with a circumstance truly ridiculous. As we consider ourselves fair game, the adventure amused us highly; and should it relax your muscles, you may laugh to the utmost without hurting our feelings, or wounding our self-consequence.

Whilst we were preparing for our walk at the hour of six, we observed a party of young Irish recruits (three or four hundred, who had arrived in Chester on the Saturday, and were going towards Bristol) drawn up before the windows of the White-Lion in order of march. The baggage wagons were arranged in front, loaded with their stores, and crouded with women following the fortunes of their sweethearts and husbands.

Wishing not to be considered as attached to this respectable party, we determined to expedite our departure, apprehending the soldiers would not start till after the muster-roll had been called. Buckling on our packs, therefore, we hastened out of the house, when, (as our ill stars ordained it) just as we had gotten into the street, the drums struck up, the word of command was given to march, and the battalion setting off swept us before them with the force of a torrent. Our attempts to return were without success, the street was narrow, and all opposition to the proceeding body vain; we were compelled, therefore, to mingle with the throng, and marched on amid the shouts and huzzas of the surrounding mob, the gibes and jokes of our Hibernian companions, quizzing our unmilitary appearance, and the benedictions and good wishes of the old women, who pitied and lamented the fate of us poor Irish bloods going to the West Indies to be food for powder, or to die by the yellow fever. Having paraded through a great part of Chester in this numerous society, we at length came to a spot where two streets intersect each other. Here was an opportunity for escape; giving a signal, therefore, to my party, we darted down the fortunate opening with the rapidity of a shot; but not without a parting salute from our Irish companions, who did not take leave of us in the politest terms.

Being fairly out of the city, we proceeded towards Hawarden (or Harden as it is pronounced) a town about six miles and half from Chester, the foot-way to which runs for the most part by the side of the Dee. The country for the first four miles is flat and tame, when the noble woods of Hawarden Castle, the seat of Sir Stephen Glynn, bart. with the small but beautiful ruins of the fortress towering above them, produce a fine diversity in the scene. The mansion approaches close to the road on the right, a handsome well-built square house. To the left rise the remains of the castle, the woods and walks of which are connected with the pleasure-grounds round the house by an elegant stone arch or bridge, crossing the road at a height sufficient to allow any kind of carriage to pass under it. Here we were much pleased with the skill and taste displayed in the management of the ruin. It is a Norman remain, dismantled by a vote of Parliament in 1645; the dongeon of which is in a beautiful stile of architecture. In order to allow a peep at this from the road, a breach has been made in the outward wall, through which the passing traveller can admire its fine circular tower mantled with a venerable mass of ivy. It is not so much exposed, however, as to leave nothing to imagination, or to preclude that interest which the mind takes in an object, when fancy has some room left to indulge her operation with regard to it.

Leaving the town of Hawarden, (where there is a foundery for pieces of ordnance) the country began to lose its tameness. On the right we had the Chester Channel, and immediately before us the mountains of Flintshire. Three miles from Hawarden, we ascended Buckley hill, in order to visit the large potteries scattered over the face of it; fortunately we met with the master of the works on the spot, who was so good as to conduct us round the manufactory; and explain to us the process pursued in forming the various articles which it produces; such as jugs, pans, jars, stone bottles, &c. &c. The clay used for the purpose is of three kinds, differing from each other in their power of resisting the action of fire. The most tenacious is called the fire-clay, which forms the earthen receptacles and stands that receive and support the articles whilst they are baking. The second is a less enduring species and called the stone-clay, of which the jars, pickling-mugs, whisky-cans, &c. are made. The third, least capable of resisting heat, affords material for the smaller glazed potteries. The mode of glazing the second sort of articles is by strewing a quantity of salt (in the proportion of two hundred pounds to eight hundred pieces if pottery) over the articles when they are heated to the highest degree, which dissolving, distributes itself through the whole mass, and becomes fixed in the form of a shining incrustation or varnish. A method altogether different glazes the smaller pieces; that of dipping it into a liquor composed of pulverized lead and water, before they are exposed to the fire. Having magnus mixed with it, this liquor gives the ware a black glaze, and without the addition it renders it of a light yellow colour. The articles are not, however, totally immersed in this preparation, as the lead being melted, would (in that case) occasion the ware to adhere to the earthen stand on which it is placed. Towards the bottom, therefore, a space is left (as may be seen every day) untouched by the glazing liquor; when thus prepared, the articles are placed in brick-kilns, formed like bee-hives, and heated to the requisite degree. Here they remain forty hours, when they are taken out, gradually cooled, and packed up for the market.

The clay for all these purposes is found in the neighbourhood, and prepared for manufacture in the following manner:- The workmen first place it in a circular cistern, called the bulging pool, when, whilst covered with water, it is kneaded by a cylindrical machine, which performs a double revolution round its own axis, and an upright pole in the centre, and pounds it completely. It is then tempered by boys, who tread it under their naked feet for some hours, and lastly, it passed through fine silk sieves, to free it entirely from dirt, stones, &c. The articles are formed in a lathe by hand, with the assistance of a flat stone, which has a rapid rotatory motion in a horizontal direction.

We now descended the north-western side of Buckley mountain, enjoying the rich prospect spread beneath us -- the vale of Mold, a fertile length of country ornamented with woods, villages and elegant mansions. Mold itself, with the mound on which its ancient castle stood, and the great cotton manufactory a short distance from the town, were striking objects in the beautiful and diversified picture. The church, the only building of curiosity in the place, is of the fifteenth century, elegant and uniform, consisting of one middle and two side aisles, and a square tower at the west end. Its interior is most superbly fitted up and ornamented, exhibiting much good carving both ancient and modern; some painted glass, and a fine marble monument of Robert Davies, esq; the only defect in its flat ceiling, which produces a most unpleasant effect to the eye, and deadens greatly the sound of the voice.

Taking the road to Llyn-y-Pandu mines, we had an opportunity of surveying (about one mile from Mold) Maes Garmon, the spot on which a celebrated battle was fought, in the year of our Lord 420, between the Britons headed by Germanus and Lupus, and an army of Saxons and Picts, who had united their forces and were carrying desolation through the province. The contest is said to have taken place during Easter week, when the soldiers of Germanus, at the command of their leader, repeated the word Allelujah as they rushed upon the foe, with a full persuasion of its powerful efficacy; so terrified the Pagan host, that they fled at the third repetition of it, and were pursued by the conquering Britons with terrible slaughter. A pyramidical stone monument, commemorative of this wonderful event, was erected on the spot by the late Nehemiah Griffith, esq; near whose seat, Rhual, the place is situated, which bears the following inscription:-

Ad Annum

CCCC XX

Saxones Pictique Bellum adversus

Britones junctis viribus susciperunt.

In hac regione hodieque MAES GARMON

Appellata; cum in praelium descenditur,

Apostolicis Britonium Ducibus Germano

Et Lupo, Christus militabat in Castris;

ALLELUIA tertio repetitum exclamabant

Hostile Agmen terrore prosternitur;

Triumphant

Hostibus fusis sine sanguine

Palma fide, non viribus obtenta

M. P.

In Victoriae Alleluiaticae memoriam

N. G.

M DCC XXXVI

Another hour brought us to the great object of our days ramble, Llyn-y-Pandu mine, the most considerable lead-mining speculation in England. The scenery of this place is wonderfully wild and romantick; a deep valley, rude and rocky, shut in by abrupt banks, clothed with the darkest shade of wood. Straggling through the bottom of this dale, is seen the little river Allen, which, having pursued a subterraneous course for nearly three miles, makes its second appearance close to the lower engine belonging to these stupendous works.

Llyn-y-Pandu mine is the property of John Wilkinson, esq; the great iron-master, who has, with infinite spirit and perseverance, encountered obstacles in bringing it to its present state, that would have exhausted the patience and resolution, as well as the coffers, of most other men. With all his exertions, however, he has not been able to render it compleat; the mine even now contains so much water, that he has been under the necessity of erecting four vast engines (of Messrs. Boulton and Watt's construction) upon the premises to drain it. The steam cylinder of the lower one is forty-eight inches diameter, and works an eight-feet stroke in a pump twenty-one inches diameter, to a depth of forty-four yards; the steam cylinder of the Mountain engine is fifty-two inches diameter, and works an eight-feet stroke to a depth of sixty yards; the steam cylinder of Perrin's engine is twenty-seven inches diameter, (double) and works a six-feet stroke in a pump twelve inches diameter to a depth of seventy yards; and the steam cylinder of Andrew's engine is thirty-eight inches diameter and works an eight-feet stroke to a depth of sixty yards. The mountain engine has been lately erected, in consequence of a lease of ground, of upwards of a third of a mile in length upon the range of the Llyn-u-Pandu vein, called Cefn-Kilken, granted by Earl Grosvenor to Mr. Wilkinson. Many thousands of tons of lead ore are now in stock upon these premises waiting for a market, the war having almost suspended the demand for lead, and lessened the price to nearly one half of what it formerly sold for. The engines also are quiet, and the works at a stand. When the bottom level, intended to communicate all the engines, is finished, great expectations are entertained with respect to the produce of this mine; as it contains one head of solid ore upwards of six feet wide, another of four feet, and about two feet upon the average for ninety yards in length upon the bottoms. The ore is of two kinds, the one blue, which yields sixteen cwt. of lead per ton, and other white, which yields thirteen cwt. They are both gotten in the same vein; the white lying in general on the south, and the blue on the north side. When peace shall have again opened a market for lead, these ores are intended to be smelted at works now erected by Mr. Wilkinson on Buckley Mountain, near to the road which leads from Mold to Chester.

One of the vast engines I have described has a particularly striking effect, from the singularity of its situation; standing detached from every other trace of human art, in the bottom of the valley, immediately at the foot of a huge perpendicular lime-stone rock, which rears its broad white face above the apparatus to a considerable height. In the neighbourhood of this work we picked up some good fossil specimens, a perfect bivalve of the cockle kind, and an elegant species of the astroite or starstone, beautifully striated and intagliated from the polygonal edges above to a centre in the bottom.

A little lower down the river, and adjoining to Llyn-y-Pandu, is a lead-mine called Pen-y-Fron, belonging to Mr. Ingleby. This is drained by a steam-engine upon the old construction, and a water-wheel. The steam cylinder of the engine is sixty inches and half diameter, and works one sixteen-inch and two fourteen-inch pumps, to a depth of forty-four yards; the water wheel works two twelve-inch pumps to the same depth. Independent of these, are two other wheels, which raise the water from the lower workings to a main level, communicating with the engine. With all this power Mr. Ingleby is scarcely ever able to get to the bottom of his work, except the weather be particularly dry. Were he able to effect this completely his profits would be immense, since the mine is incalculably rich, there being one vein of solid ore two yards and a half in width; besides several smaller seams. In the few instances where Mr. Ingleby has gotten to the bottoms, no less than seventy tons of ore have been raised per week. The blue ore of this mine is not so good a quality as the same species at Llyn-y-Pandu, owing to its containing a small portion of black-jack; of white ore Pen-y-Fron mine has but a small quantity.

The great convenience of these works is their compactness. The ore being dug, and the article manufactured, nearly on the same spot. Smelting-houses are in the immediate neighbourhood of the river, for fusing the ore, and casting it into pigs; and about half a mile below these premises is a mill, worked by a water-wheel for rolling the lead into sheets.

After a compleat survey of these valuable works, we directed our steps to Caerwys, where we intended to remain for the night, and arrived here after a walk of great variety and amusement, of which the last six miles exhibited a constant succession of the most beautiful and romantick scenes.

Having secured beds we rambled through the village, in order to discover some traces of its former magnificence; but our search was in vain. The glory of Caerwys is faded away, and nought remains to evidence its former consequence except the name, which it continues to bear. Stat nominis umbra. This is a compound of the two words caer, a city, and gwys, a summons, notifying its having been formerly a place of judicature. The great session or assize for the county of Flint, was for many ages held in the town of Caerwys; and it still continues to be one of the contributory boroughs for the return of a representative to the national senate.

But the chief boast of the town was, its being the Olympia of North-Wales, the theatre where the British bards poured forth their extemporaneous effusions, or awakened their harps to melody;

"And gave to rapture all their trembling strings,"

in the trials of skill instituted by law, and held at this place, with much form and ceremony, at a particular period in every year. This meeting was called the Eisteddfod, where judged presided, appointed by special commission from the princes of Wales previous to its conquest, and by the kings of England after that event. These arbiters were bound to pronounce justly and impartially on the talents of the respective candidates, and to confer degrees according to their comparative excellence. The bards, like our English minstrels, were formed into a college, the members of which had particular privileges, to be enjoyed by none but such as were admitted to their degrees, and licenced by the judges.

The last commission granted by royal authority for holding this court of Apollo, seems to have been in the 9th of Elizabeth, when Sir Richard Bulkley, knt. and certain other persons, were empowered to make proclamation in the towns of North-Wales, that all persons intending to follow the profession of bard, &c. should appear before them at Caerwys on a certain day, in order to give proofs of their talents in the science of musick, and to received licences to practice the same. The meeting was numerous, and fifty-five persons were admitted to their degrees.

From this period, I apprehend, the meeting at Caerwys faded away; the minstrel ceased to be considered as a venerable character in England, and our monarchs looked, probably, with equal contempt on the bards of Wales. Thus neglected and despised, the Eisteddfod dwindled to nothing, and reposed in oblivion for many years. Of late, however, some spirited Welsh gentlemen, who had the honour of their national harmony at heart, determined to revive a meeting likely to preserve and encourage that musical excellence for which their countrymen have been so deservedly famous for many centuries. This spring their resolution was carried into effect, and an Eisteddfod held at Caerwys, the ancient place of meeting; the ceremonies and proceedings of which were as follow:-

"In consequence of a notice published by the gentlemen of the Gwyneddion, or Venedotian society in London, the Eisteddfod, or congress of bards, commenced at Caerwys, on Tuesday 29th of May, 1798. Ancient custom requires, that the notice should be given a twelve-month and a day prior to the holding of the meeting. The ancient town-hall was properly prepared for the company, which was very numerous and respectable, by the judges appointed by the above society, to whose activity and publick spirit on this occasion too much praise cannot be given.

The first day was taken up in reading and comparing the works of the different candidates for the gader, or chair. On a subject so congenial to the spirit of the ancient Britons, as "the love of our country, and the commemoration of the celebrated Eisteddfod, held at the same town and under the same roof by virtue of a commission from Queen Elizabeth" the thesis judiciously fixed upon by the Gwyneddigion , it was natural to suppose that the productions would be numerous and animated; which proved to be the fact. After mature deliberation, the judges decided in favour of Robert ap Dafydd, of Nantglyn, in Denbighshire, known among the bards by the name of Robin Ddu o Nantglyn. The next to him in point of merit was Thomas Edwards o Nant, by some called the Welsh Shakespeare, on account of the superior excellence of his dramatick pieces in the Welsh language. Towards the heel of the evening, the bards, when their native fire was a little heated with cwrrw da, poured forth their extemporaneous effusions on subjects started at the moment; which, though truly excellent of their kind, reminded the classical scholar of the poet mentioned by Horace, who composed two hundred lines stans pede in uno. Of these productions, the Englynion, or separate stanzas, on Mr. Owen Jones, of London, the gentleman who was the principal encourager of the meeting, as having contributed twenty pounds to be distributed according to merit, in prizes to the different competitors, deserve the most eminent place.

On the second day, the vocal and instrumental performers exhibited their powers; and after a contest of twelve hours and upwards, Robert Foulks, of St. Asaph, was declared to be the pencerdd dafod, or chief vocal performer; and William Jones, of Gwytherin, to be the pencerdd dant, or the chief harper.

This Eisteddfod was well attended; the number of the bards amounting to twenty, of the vocal performers to eighteen, and of the harpers to twelve.

Several connoisseurs in musick, who were present, declared that they never recollected a contest of this nature to be better maintained, or to afford more amusement."

But though Caerwys is as it were the focus of harmony, the theatre where musical talent has been so often and so highly displayed, yet the circumstance does not seem to have inspired any of its inhabitants with a love for the science; since, in spite of all our enquiries, we are not able to find a person who can regale us with a tune upon the harp.

The little family at our head-quarters (the Crossed-Foxes) has interested us extremely. It consist of a widow woman, her son, and daughter; the former is a middle-aged person, with a cast of melancholy in her countenance, and a humbleness of manners, which indicate a knowledge of better days, but at the same time a perfect resignation to her present situation. The daughter, a sweet-tempered, modest little girl, about seventeen; the boy a sprightly and sensible lad of thirteen or fourteen. There is no surer road, my friend, to the confidence of an honest heart, than by taking a real interest in its feelings. The poor woman saw that our enquiries were not the result of impertinent curiosity, and therefore told us, without reserve, her short and melancholy story.

Two years since, she observed, she was living in credit and comfort, with a kind and tender husband, and a son grown to man's estate, dutiful and affectionate, the darling of herself, and beloved by all the country around. Her husband, who had been brought up in the mine agency business, had just obtained an appointment which cleared him about three hundred pounds per annum, and an establishment of a similar nature was promised to the eldest son. The other children, a daughter since married, and the two younger ones, were placed in the best schools in the country; and nothing seemed wanting to compleat the happiness of the little contented family. In the midst of this halcyon but deceitful calm, her husband caught a violent cold in one of the mines which he superintended; a fever succeeded, and in a few days he was judged to be in danger. During the sickness of his father, the elder son, who doated on him, was riveted to his bed; he nursed and attended him when awake, and watched by his pillow while he dozed; administered his medicines, and prepared his food. Two days confirmed his prediction, for on the evening of the second the affectionate son witnessed the expiring struggle of his beloved parent. From this moment the youth was never heard to speak; he did not weep, indeed, but the deep convulsive sighs which burst occasionally from his bosom bespoke the unutterable grief with which he was oppressed. Nothing, however, could prevent him paying the last duties to his parent, and attending the corpse to the adjoining church-yard. But reason was unequal to this effort, the solemn ceremony of interment, the weeping croud around, and the chilling sound of the earth rattling on the coffin, when the body was consigned to its final home, destroyed his poor remains of sense. He uttered a heart-piercing shriek, and started into a paroxysm of the wildest phrenzy. Providence kindly ordained that his sufferings should not be long; a raging fever immediately attacked him, and in a few days carried off this unhappy victim of filial affection. Thus deprived of her protector, and the means of supporting her family, the disconsolate widow was suddenly reduced from happiness and independence to affliction and want, and constrained to enter upon the situation in which we found her, in order to procure a precarious and scanty maintenance for herself and her children.

During our former, as well as present progress through Flintshire, we have had occasion to observe that English is very generally spoken by all classes of society; in so much, as nearly to supersede the use of the national tongue. We were unable to account for this circumstance till today, when our landlady's sprightly son acquainted us with the cause of it. One great object of education, it seems in the schools (both of boys and girls) of North-Wales, is to give the children a perfect knowledge of the English tongue; the masters not only having the exercises performed in this language, but obliging the children to converse in it also. In order to effect this, some coercion is necessary, as the little Britons have a considerable aversion to the Saxon vocabulary, if, therefore, in the colloquial intercourse of the scholars, one of them be detected in speaking a Welsh word, he is immediately degraded with the Welsh lump, a large piece of lead fastened to a string, and suspended round the neck of the offender. This mark of ignominy has had the desired effect; all the children of Flintshire speak English very well, and were it not for a little curl, or elevation of the voice, at the conclusion of the sentence (which has a pleasing effect) one should perceive no difference in this respect between the North-Wallians and the natives of England. The pride of the Englishman may, perhaps, be gratified by so great a compliment paid to his vernacular tongue; but the philosopher will lose much by the amalgamation that is rapidly taking place in the language and manners of Wales, and our own country.

Your's, &c.

R.W.

Author: Warner, Richard

Tags

Year = 1798

Month = September

Document = Map

Event = Leisure

Landscape = Natural

Work = Light Industry

Extra = Pre 1900

Copyright © 2015 The Buckley Society