Buckley Society Magazine Issue Four: Observations on Coalmining Methods and Conditions in Seventeenth Century Flintshire: Fig 1 by Ken Lloyd Gruffydd"

Flintshire

April 1976

Buckley Society Magazine Issue Four, April 1976

p.36 - 42

see 28.32 for contents etc.

Observations on coalmining methods and conditions in seventeenth century Flintshire.

K. Lloyd Gruffydd

A new era in Flintshire coalmining was mooted during the reign of Elizabeth I when the shaft-technique of sinking pits was introduced into the county. The effects of this on various aspects of the coal-mining scene quickly materialised. Costs invariably rose and only the gentry, and those with substantial financial backing, were able to continue operating their mines. Efforts to overcome the problem emerged in the formation of partnerships, but even these dwindled considerably after economic commitments incurred during the Civil War. Inland workings such as those around Ewloe, Hope and Mold had always been limited in extent and more or less operated to provide domestic fuel for their owners.

Closure of the less enterprising pits meant that miners had to seek employment elsewhere. In the past, agriculture had provided an alternative, but the trend towards pastoral farming at this time offered few opportunities. There was therefore little left for them to do but find work in those areas where the most prosperous pits were located, generally along the Dee coastal strip where easy access to water transport promoted the export trade.

It was not hard for some of the redundant husbandmen to adapt themselves to this kind of employment because they had previously been associated with the sale of coal, carting it during the winter months when the work on the land was suspended during inclement weather.

Unlike the lead-miners who on occasion had organized themselves as occupational communities at Holywell and Hope as early as the fourteenth century, those associated with coal travelled considerable distances to their work. As the coalmines were sunk deeper, expanded and became more productive however, nucleated settlements comprised entirely of coalminers, their wives and dependants, emerged at Mostyn and on the outskirts of Flint and Holywell. A 'new village' at the latter was known as Pentre Pwll Glo (Coalpit Village), and by Edward Lhuyd's day comprised up to twenty houses.

Meager information is available concerning the social life within these newly formed communities. It would seem that the authorised keepers of law failed to exercise their prerogative in such closely-knit societies. So much so, that the inhabitants behavior at times was abominable leading them to be referred to as 'those ill Condisioned Collyars'.1 A violent incident at Bychton in 1634 illustrates this aspect of their life. One Piers ap John, after coming up 'in a hook' from the bottom of a pit, got into an argument with the reeve, William David ap Rees. The latter struck Piers who reacted by taking

'up a woodden barre, and did give the said William David ap Rees therewith a

blowe upon the heade, so that. thereby (he) fell downe headlong into the

Colepitt; and was taken upp dead.'2

It is little wonder therefore that the life led by these people instilled in them a built-in resilience to hardship. However, they were not without religion and by 1630 there even existed a sufficient number of English speaking colliers in the parish of Flint for Somerford Oldfield (owner), Edward Cotton (reeve) and others of the Bagilit coalpits, to come to an agreement concerning an annual endowment of £4 16s 0d., which was payable on the first Sunday in every month at the North Porch of the Church or Chapel of Flint. This was

'to procure a learned preacher of the Word of God, who shall be of honest conversation and conformable to the Laws and Canons of the Church of England, to preach a Sermon or Lecture in the English tongue in the Church or Chapel of Flint aforesaid.'3

It would appear that it was during this period that one witnesses the reintroduction of outside experts and workmen into the Flintshire coalfield since the days of Edward I. The lead-mining industry on the other hand had always drawn upon a constant stream of imported labour.

The collier's wages were extremely low and more than often correlated to a pit's weekly output (i.e. 6 days' work.) Therefore earnings were not guaranteed. Work began at 6 am and ended at 6 pm, with an hour at noon for rest. It was also customary for them to be given an opportunity of eating 1½d worth of bread and the sharing of 4d worth of drink amongst a dozen men. 4

No doubt the extraction of coal by means of the medieval system of bell-pits was still in use in Flintshire well into the seventeenth century, and the application of the term 'a Colepitt Cheyne' made in 1632 possibly verifies this.5 The areas most likely to have employed this method of mining were those located inland, where the workings were small and therefore simplicity and cheapness became a vital key to their existence. To be successful, the enterprising coal owners had long realised that the implementing of new techniques was imperative for prosperity. Shafts had been introduced at Mostyn as early as the 1570s. By 1580 one such shaft there had descended to 90ft (27.4m),6 and during 1640 a depth of l20ft (36.5m) was recorded; the workings were by now reputedly operating under the River Dee.7 By 1675 a third 'roach' (seam) had been reached at an approximate depth of 200ft (60m).8

Coal appeared at various places in Flintshire as surface outcrops, and all that was necessary to retrieve it was for levels to be driven into the incline resulting in many of these sites resembling a quarry rather than a coalmine. Examples of this occurred at Holywell, Mostyn and Whitford in the north of the county and Mancot, Northop, Mold and Ewloe in the south.

From observations made at the Great Sessions held at Flint in 1632, one can assume that little regard was paid to the medieval laws of re-filling worked pits. In Buckley for instance

'..a Waine leading from Knoule Hill to Eastyn (Caergwrle) and from there to Wrexham full of ould Colepitts.... their are within the Townshipps of Bannell and Pentrehobin and bene Dangerous for travoylers and passingers when passeth that waye.'

At Sychdyn, Griffith ap Robert and seven fellow colliers had been equally neglectful with abandoned pits '...for they are not flilt up and Crowned.'9

The name 'the Deepe Workes' in the Manor of Ewloe10 suggested something other than a bell-pit, whilst 'whele pit wood' signifies a mechanical means of extraction. A mine located at the latter, and defunct by 1625,11 was probably the old Crown mine mentioned in ancient leases. Also, works at Ewloe during the period of the Dutch Wars were deep enough to encounter flooding and caused concern for their owner who in a letter from Holland enquired, 'I hope the Coalpitts are overcome.'12

The larger pits were generally worked by up to twenty men under the watchful eye of a reeve or overseer. Some hewed and cleaved along the seams, others collected the coal into corves or pytches (willow baskets) and brought them to the bottom of the shaft where they were hooked or tied to ropes and hauled to the surface - a very hazardous occupation at the best of times, due to the unreliability of the ropes. A couple of men would be employed at the top to separate the coal and slack (culm), stacking them in different piles. A sizeable and efficiently run pit at this time would produce some ten to twelve tons per day,13 while it would take a smaller one six days to reach a comparable output.

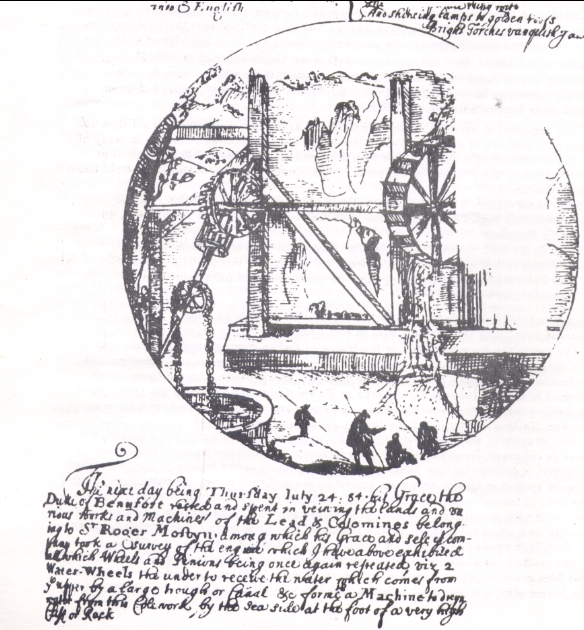

The methods employed in winding the coal and excess water to the surface obviously varied from place to place. The popular means adopted in Flintshire consisted of a winch at the lesser pits, a waterwheel or horse-worked whimsey at the more advanced workings.

Examples of the first mentioned were seen at Hopedale in 1630 when two men were paid 7d and 4d a day respectively for winding;14 and at a coastal location in 1698 it was said

'they have..engines that draw up their coale in sort of baskets like hand harrows which they wind up like a bucket in a well, for their mines are dug down through a sort of well and sometimes its pretty low before they come to the coales.'15

Such machinery was of course unsuitable for the very deep mines as manpower was inadequate to bring coals up. Horses were used for this purpose, but were uncommon and for our descriptions of them one must rely on similar ones used in the county for the extraction of water from pits. To a layman they had

'great wheels that are turned with horses that draw up the water and so

draine the Mines.16

but the more mechanical mind saw

'a horse engine of substantial timber and strong ironwork, on which lay a trunk or barrel for winding the rope up and down, of above l000lb weight.. .one bucket going down and the other coming up full of water. This trunk was fastened to the frame with locks and bolts of iron.'17

The last mentioned engine operated at one of the Mostyn pits but was destroyed in 1675. By 1684 it had been replaced according to the observations of the Duke of Beaufort by two

'Water-wheels, the under to receive the water which comes from ye upper by a large trough or Canal & formeth a Machine to dreyn water from this Cole work by the sea side at the foot of a very high Cliff or Rock'.18 (see Fig 1).

Indeed the pits throughout the county encountered water trouble and prompted Edward Lhuyd to remark in 1698, 'mae yno dhigon o lo ond bod gormod o vroth.'19

Water in the mines also meant extra hazards for the colliers. This came in the form of firedamp; a mixture of dampness and mephitic vapours which was particularly prevalent during the summer months. At first the dangers from this phenomenon were not realised, and the workers used to amuse themselves with the bright shooting flame that 'popped' and shot away from the candle when the vapour came into contact with a naked light. More respect was paid to firedamp or 'Y Ladi Wen' (The White Lady) as it was called, after an incident that took place at Mostyn in 1640.20

Having gone down some considerable distance, much water was encountered and fire-damp spread rapidly. The first collier to descend was immediately met by the firedamp which

'darted out violently at his candle that it struck the man clean down, singed all his hair and clothes and disabled him from working hereafter.'

After this they took more care and adopted a method by which candles were lowered down the shaft by means of ropes. Yet

'When they had lowered these down a little way...up comes the damp in full body, blows out the Candles, disperseth itself about the Eye of the Pit, and burneth a great part of the men's hair, beards and clothes.., in the meantime making a noise like the lowing or roaring of a Bull but lowder, and in the end leaving a smell behind it worse than of a carrion . . .after this the water that came up at the other pit was found to be blood warm if not warmer... and the crevices of the rocks where the damp kept were all about fire-red Candlemas Day following.'

For a period the problem was solved. One man dressed in clothes and rags saturated with water entered the pit one hour before the morning shift began. Armed with a candle at the end of a long pole, he proceeded to ignite the firedamp. The explosion's magnitude varied according to the quantity of the accumulated gas and to dodge the flame the 'fireman' (as he was called), lay flat on the floor while it flashed along the roof above him. This safety precaution was adopted and practised well into the eighteenth century, and at some locations even into the early 1800s, until mine owners realised the true value of ventilation shafts. We have a documented example of such an explosion from Mostyn in February 1675.21 This was perhaps not the time of the year one would have expected it to have happened.

Shortly after reaching a new depth at one of the pits there, the workers found difficulty in breathing because of the dampness and subsequent lack of air. So much firedamp had collected over the weekend that it was found necessary to fire it, but the explosion that followed resulted in a temporary abandonment. Anxious that work be resumed, the steward and two of his men went down to survey the situation

'but the rest of the workmen that had wrought there, disdaining to be left behind in such a time of danger, hastened down after them, and one of them, more indiscreet than the rest, went headlong with his candle over the eye of the damp pit, at which the damp immediately catched, and flew over all the hollows of the work. with a great wind and a continual fire, and a prodigious roaring noise.'

On this the men immediately threw themselves on to the ground or behind posts for protection.

'...nevertheless, the damp returning out of the hollows, and drawing towards the eye of the pit, it came up with incredible force, the wind and fire tore most of their clothes off their backs, and singed what was left, burning their hair, faces and hands, the blast falling so sharp on their skin as if they had been whipped with rods; some that had least shelter were carried 15 or 16 yards from the first station, and beaten against the roof the coal and sides of the posts, and lay afterwards a good while senseless... As it drew up to the day pit, it caught one of the men along with it that was next to the eye, and ascended with such a terrible crack, not unlike, but more shrill than a cannon, so that it was heard 15 miles off along with the wind, and such a pillar of smoke as darkened all the sky for a great while. The brow of the hill above the pit was 18 yards high, and on it grew trees 14 to l5yards long, yet the man's body and other things from the pit were seen above the tops of the highest trees, at least 100 yards. On this pit stood a horse engine of substantial timber and strong ironwork... yet it was thrown up and carried a good way from the pit'.

A similar explosion seems to have occurred at Hawarden during the latter half of the seventeenth century when

'Mr Thomas saw one a Pillar of Smoak, Coal, Sticks, etc., raised to a great height... all ye g(uns) of Ches(ter) would not have made so great a Rep(ort). It might have been heard ten miles round.

The Pit was near ye town and ye inhabitants imagined all their houses shook.'22

APPENDIX A

Two manuscripts deposited at the Record Office in Hawarden under the reference Clwyd R.O. Glynde MSS 3311-12., give interesting accounts of the coal workings on the lands of the Trevor family of Plas Teg during 1630-33. Their exact location is not given but somewhere where in the Coed Talon district may be a safe assumption. The only two place-names mentioned are Estyn and Gwysaney.

During the period covered by the documents some half dozen pits were sunk, the deepest 69ft (21m). Water was encountered in one instance after only going down to a level of 37ft (10.7m).

The initial procedure when opening a new pit was to carry away the topsoil. This was done in carts for which the worker was paid 5d a day. Then came the more skilled job of doing the actual sinking. Two men were usually engaged for this and were paid according to the depth achieved; 1s 6d the yard was a typical rate, although 4s 0d was recorded in one instance. Some a of the shafts were permanently propped with timber, whereas others, if the sides were relatively sound, were removed, e.g. 'to William Thomas for a day and a halfe in helpinge to gett the timber out of the new pitt at eightpence the daye.' Before the pit could be regarded as workable other safeguards had to be taken into consideration. Water was frequently encountered and various means of getting rid of it were witnessed. Sometimes a sump (hollow) or a 'draw in the bottom of the shaft enabled water to collect in one spot making it easy for a man to fill up buckets lowered by rope. In this way the water was brought to the top. One item in the accounts shows 4d 'to a Cowper for setting two hoopes uppon a barell to winde water' and another 2d 'for a bowle dish to lade water'. Other less stringent methods included driving towards the hollows and entering a wicket or adit towards the deep.

The use of candles alleviated the burden of underground work. Wickets were driven with and across seams where the rock formation permitted. Hewers earned 1s 0d for the getting of every ton while others were paid 1d the ton for 'scaring' the same. This probably entailed dressing the coal down to suitable sized lumps.

The tools of one pit were listed as follows:

3 mallets14 picks20 wedges

5 spades 2 ropes2 hooks to the ropes

Picks and spades were sharpened once a week for which the smithy was given a pytch of coal to do the work.

The pits themselves were closely sited, very similar to bell-pits, for it only took one man two days 'in dryvinge a tunnell betwixt two pits'. Once all accessible coal had been retrieved the timbering of the shaft were removed and re-used, the old shaft being filled in.

A typical six-days' work is seen in the following:

September the fourthe (1630)£sd

To John ap Ellis for sinckinge a pitte of three

and twentie yards deepe att foure shillinges the

yarde batinge one shillinge, in all he to have 4 11 0

the timber layde upon the banck.

To John Soutkerne for a boult to weinde with all

gudgins & hoopes of Irone for the fatchinge of it 6 8

For a roppe weighing Thirtie foure pounds att

feivepence the pound. 14 2

For makinge of foure peitches of a bigger sise

at six pence the peitch 2 0

To John Rees ap Flugh for eighte dayes in Cutting

Cleavinge and Careinge down of timber for to 5 4

sincke the pitt att eight pence the daye 4 0

To John Tydir for the like for the like (sic)

time att six pence the daye 4 0

For sharpninge the tooles in sinckinge 10

£6 4 0 (£6.20)

Slackness of trade often meant large stacks of unsold coal, most of which was in the form of very fine lumps. On one occasion a remark was made concerning 'a greate deale of sleake uppon the banke if it were all Sold, verye neighe Ten pounds woorth'. At 2d per ton this meant 1200 tons!

A year's accounts presented by the mine overseer show 19 pytches going to the blacksmith for sharpening tools, 'all the rest my Ladie had which ware 235 tunn and 2 pitch.' The price and quality of coal were under constant review. Specific standards were 'sett downe' and stringently adhered to. Mr Davies of Gwysaney had a man sent 'to trye the Coale' before it could be sold.

By the end of the seventeenth century one can state that the mining and selling of coal had become an 'organised industry.'

APPENDIX B

The price of coal during the period remained stable. The '6d for 2 bushells' mentioned by Celia Fiennes in 1698 can probably be explained as '6d for 2 barrells.'

YEAR PRICE PER TONSOURCE

1633 Summer 1s 0d ClwydR.O. Glynde M.SS.3311-3312 Winter 1s 3d

1654 1s 0d Clwyd R.O.Talacre MS.428

1655 1s 4d NLW Wales 4/985/1/-

1698 2s Od Celia Fiennes Journey.p 182.

The prices at Chester were invariably higher. Transportation, merchants' profits, etc., meant that as early as Elizabeth I's reign the cost was more than double that of the Flintshire Coalfield.

1588 3s 4d PROExcheq.(K.R.)Port Bks.3i/32-5

1593 4s 0d Chester City R.O. SF/42

These prices also included various taxes imposed by both Crown and City. Before 1588, when Chester came under the national customs system, the impost on coals had been 2d per chaidron but in that year it was raised to Id, whether it entered the City by land or sea.23 It was the duty of the local Sargeant of the Peace to have four of the City's standard barrels of measure in readiness to gauge the coals.24 In 1587 there were nine Chester barrels to the ton but in January of 1591 the 'salt measure' i.e. 8 barrels = 1 ton, was to be the 'coal measure' as well.25 lf this stipulation was not adhered to, then there was

'fyve shillings to be forected and payde to every owner of such Coles refusinge to measure therewith.'26

Further levies came in the form of charges pertaining specifically to Chester. In the sixteenth century a ½d toll was collected on 'every stoune cole' that entered the City, it having been a 'graunt of ye citie & used tyme out of mind.'27 By 1691 the Town Crier, by virtue of his office, was entitled to a duty on all foreigners' teams coming into the City with coals. The rates were 1s0d for every ox-team carrying above 1 ton, and 9d, 8d or 6d for every other load, according to its size.28 The boatage on coal there in 1693 was recorded at 2s 0d.29

(The export of coal and its prices will be dealt with in a later study)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1 Dodd, A.H. Studies in Stuart Wales (1952), p28.

2 N.L.W. Wales 4/981/3/-.

3 N.L.W. MS. 6281E.

4 Owen, D.G. Elizabethan Wales (1964), p.l52; Rees, W. Industry before the Industrial Revolution (1968), Vol.1, p.123.

5 N.L.W. Gwysaney Letters & Papers. 35A.

6 N.L.W. Wales 4/970/3/-.

7 Clwyd R.O. DC/197/ p.490.161.

8 Galloway, R.L. History of Cailinining in Great Britain, p.71.

9 N.L.W. Wales 4/980/8/-.

10 N.L.W. MS. 9060E.

11 N.L.W. MS. 466.

12 N.L.W. Gwysaney Letters & Papers, 33B.

13 Cambrian Register Vol 2, p.107.

14 Clwyd R.P. Glynde MS. 3311.

15 Morris, C.(ed.) Journeys of Celia Fiernes :1698 (l947). pp.l81-2.

16 ibid.

17 Galloway, R.L. Annals of British Coalmining, p.222.

18 Banks (ed) Account of the Official Progress of his Grace Henry the first Duke of Beaufar through Wales in l684 ,as recorded by T. Dineley (1875), p.95.

19 Lhuyd, E. Parochialia PL2, p.86.

20 Philosophiail Transactions No.136 (1677), p.895, quoted in Bye-Gones(1882), p.ll5 and Galloway's Annals, &c., pp. 220- 23.

21 ibid.

22 Lhuyd, E. Parochialia Pt. 2, p.95.

23 Wilson, K.P. The Port of Chester in the Middle Ages Vol. 1, p.l44. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis (Liverpool 1965).

24 Chester City R.O. A/B/1/226v.

25 ibid. A/B/1/234; SF742.

26 Morris, R.H. Chester during the Pkmtagenet and Tudor Periods, p.446.

27 Chester City R.O. A/B/1/41 -2. The '/2d toll seems to have imposed as early as 1279; see Calendar of patent Rolls (1272-80), p.436.

28 Chester City R.O. A/B/3/32.

29 ibid. A/B/3/41v.

Author: Gruffydd, Ken Lloyd

Tags

Year = 1976

Month = April

Building = Industrial

Landscape = Industrial

Work = Mining

Extra = Pre 1900

Copyright © 2015 The Buckley Society