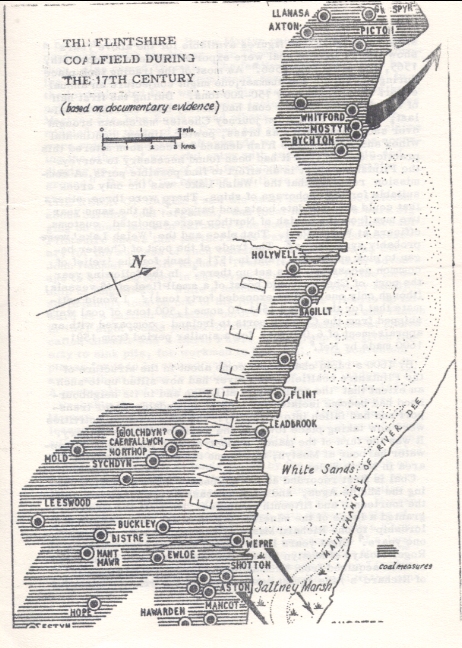

Buckley Society Magazine Issue Three: The Flintshire Coalfield during the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries by Ken Lloyd Gruffydd: map of the Flintshire Coalfield during the Seventeenth Century"

Flintshire

July 1975

Buckley Society Magazine Issue Three, July 1975

see 28.301 for contents etc

Map of the Flintshire Coalfield during the Seventeenth Century, based on documentary evidence

THE FLINTSHIRE COALFIELD DURING THE SIXTEENTH AND SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES

K Lloyd Gruffydd

THE MAJOR CONTRIBUTING FACTORS to the rise of Flintshire as a coal producing area during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were geographical. The mines were situated near to the sea shore, enabling coal to be exported to Ireland both easily and cheaply, and this coincided with that country's insatiable demand for fuel during this period. The neighbouring county of Chester cou1d boast only of a couple of small pits and Denbighshire's inaccessibility to water transport deprived that county of the means of offering any formidable competition.

Shipments left Flintshire mines from a few small creeks on the Dee estuary. These came under the Chester Port Authority, and its surviving books reveal that the trade was mainly focused on the Irish counties in close proximity to Dublin. During the first quarter of the seventeenth century traffic across the Irish Sea reached sizable proportions; but for various reasons the county of Flint failed to sustain its early successes. What chiefly accounted for this was that the Dee channel swung away from the Flintshire side of the estuary towards the Wirral, and the creeks and havens on the Welsh side became stranded because of rapid silting. This loss in trading facility was promptly exploited by the Cumberland coalfield. The navigability of the river had been suspect since the Middle Ages and by 1541 it was reported at the Privy Council that,

"the cittie of Chester and the shippes and vesselles belloning to the same be in greate decaye by reason of wante of a goode keye and havon there for the succour and harburgh of shipps"1

It was not until some twenty years later that any sort of positive action was taken, when a quay was constructed at Parkgate. The initiative was probably the direct result of Chester being brought under the national customs system in 1558.

The earliest extant customs accounts for Chester are for the years 1565-6, and information found in them suggests that vessels were no more than ten to twenty tons burthen. Most of them operated from Hilbre Island off the northernmost tip of the Wirral peninsula, as Flintshire itself possessed few suitable ships or havens. The figures available for the above years show that 71 tons of coal were exported between October 8th, 1565, and April 8th, 15662. As most of the trading took place during the spring and summer, one might conjecture an annual export of approximately 150-200 tons. During the first half of the sixteenth century coal had merely been carried as ballast, whilst on the return journey Chester merchants brought over such commodities as brass, pewter, linens, continental wines and glass3. The Irish demand for coal soon altered this practice and by 1566 it had been found necessary to survey the Flintshire coast in an effort to find possible ports. A commission reported that the 'Welsh Lake' was the only creek suitable for the anchorage of ships. There were three others that could accommodate boats and barges.4 In the same year two men from the parish of Northop were appointed customs officers at Wepre Pool. That place and the 'Welsh Lake' were probably synonymous5. The trade of the port of Chester began to pick up quickly and in 1571 a bank for the 'relief of common necessity' was set up there6. In the following year the port of Chester could boast of a small fleet of 45 vessels; (though only one of them exceeded forty tons).7 I would estimate that for the period 1561-70 some 1,500 tons of coal were shipped from the Chester ports to Ireland, compared with an appraisement of 6,000 tons for a similar period from 1591-1600 made by Nef8.

By 1600 a rapid change had come about in the structure of the Flintshire coalfield. The river had now silted up to such an extent that the ancient pits at Ewloe and in its neighbourhood had become isolated for lack of dependable water transport and had fallen into obscurity. The major mining activities were now taking place towards the mouth of the Dee estuary. It was the turn of the manor of Mostyn, with its adequate deep-water harbour at Mostyn, to become the major coal-mining area in North Wales.

Coal is first recorded as having been worked at Mostyn during the Middle Ages, and various leases were taken out in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In 1594 the Crown granted a lease of the mineral rights of the town, manor and lordship to one Richard Mason of London for a term of twenty-one years9. Eight years later Mason assigned the lease to Roger Mostyn of Mostyn for a consideration of £70; and Roger also acquired from Thomas Mason (presumably a relative of Richard's ) the 'quiet possession' of the existing mines for a bond of 200 marks10. Roger Mostyn operated the mines in conjunction with his father, Sir Thomas, and his younger brother, also named Thomas. The family were reported as having the right to the 'petticoalstone, seacole or colestone' in the lordship, but this was soon disputed in the courts by their neighbours; amongst whom were included their cousin, Piers Mostyn, Sir John Egerton and others, who had lands intermingled with those of the Crown and the Mostyns. Their claims were rejected and soon afterwards we find the Mostyns accusing the others of wrongful entry with engines, tools etc. and digging up 2,000 tons of coal from under a piece of waste ground.11 By 1616 the Mostyns had three pits.12

THE REIGN OF JAMES I saw the early fears and scepticism about burning coal forgotten, and local landowners were digging on their lands in earnest. The documentary evidence for Flintshire shows that partnerships were considered necessary for the success of such ventures. Gentry such as Sir John Hanmer and Sir Richard Trefor found it to their advantage to come together in surveying certain mines in the lordship of Englefield13, while a member of the Salisbury family surprisingly took on one of his former tenants, Henrie ap Edward as a partner sometime before 1616. At Axton and Picton in 1621 eight locals joined forces to work coalmines at places called Glasdir and Y Garth Fawr. This group was given liberty to sink pits for workmen to hew coal, with convenient places for it to be stored until sold and the right to carry it away without having to render an account to the landowner15. A partnership of eight operated at Sychdyn as well by 1632.

Probably the most speculative of Welshmen was Edward Morgan of Golden Grove near Llanasa. By 1619 he had the leases of several coalmines on his own and neighbours lands adjoining the Crown wastes in Englefield. In that year he was granted yet another licence, 'to digge and searche for Coles at his own Charge' in lands 'lying by the seaside which extend from Wapre Poole to Halywell Brooke' and was to have the 'benefitt of the Waters near adjoineinge for the better effectinge and Wynninge of anie Cole Mynes there',17. Morgan also worked some pits in conjunction with Robert Davies of Gwysaney. In 1626 they came to an agreement with a Chester man touching the construction and maintenance of a 'water worke and engines at Bagillt for the coal works there'18. A similar draining scheme was agreed upon at Afon Liwyfen and Holywell, Morgan alleging that it 'would tend to the general good of the inhabitants adjoining. His neighbours and the Commissioners of Revenue agreeing that 'it will prove very beneficial…both for fuel and for setting many poor people to work'19.

It was during this time that we find middle class Englishmen investing in Flintshire industries. Edward Morgan's partner at one of the Bagillt pits was an Edward Cotton of Ipswich20. Indeed, Bagillt seems to have been the main district for these men from outside the county to centre their energies. A local man William Johnes, and a Mr Potter had a mine there prior to 161621; while during the reign of Charles I, Wynn of Leeswood and a Somerford Oldfeeld worked coals there22. There are records as well of Englishmen being independently involved in coalmining in the county, although such instances are rare before the Restoration. During 1636-37 Francis Braddock and Christopher Kingscote, both of London, were granted Letters Patent not only to some coalmines in the lordship of Englefield, but also the right to dig for coal on the waste lands and marshes there23. A lawsuit supervened, as to whether this particular grant included the seams underneath the land lying on the sea shore at a place called 'the White Sands'; but the Crown's claim was dismissed24.

The nature of the leases varied according to the extent or prospective richness of the seams. Small workings at Y Geufron in Picton in 1654 for instance realised only 10s. per annum for the landowner, plus a ton of coal whenever he required household fuel 25. Terms usually agreed upon were for periods up to twenty years, with the rents varying from annual payments to a percentage of the coal raised at any one particular pit. Edward Morgan paid one tenth of his output for twenty years26; while at Hawarden in 1661, George Lloyd promised to give one seventh of the coal he raised to the grantor of the leaset27. Piers Mostyn gained exceptional terms for digging at Gwespyr and Picton in a later lease dated 1699. The duration was forty-one years and the rate one seventh, or the value in money thereof, of 'coal taken out of the eye of pits'. If the undertakings were successful then the regular remunerations was to be four barrels (that is, half a ton) for every six days work done28.

A noticeable and important point concerning Flintshire after the Civil War was the mortgaging of their lands by the local sentry, generally the result of debts incurred during the upheavals. This directly concerned coalmining from 1660 in that we find prosperous outsiders moving into the county to exploit its mineral wealth, a tendency that was to spread considerably during the following centuries.

By the early seventeenth century the Crown was encouraging the farming (or leasing) of coal on all available lands as the taxes from it had become a lucrative source or revenue; it was even described as 'the bravest farm the King has'29.

Economic stability since the days of Elizabeth I had resulted in a vast programme of domestic rebuilding. Crown and Parliament alike soon realised that an additional means of revenue was to be had by imposing a levy on the increasing number of chimneys that were appearing everywhere. There were some forty 'gentry houses' in Flintshire alone at this time; not counting more ordinary dwellings. The hearth-tax returns for 1664 reveal the total number of houses in the county to be 4,364.30 There is little doubt that the tax was the most unpopular ever placed on coal, as it directly concerned both the common man and the nobility.

Unless workings were extensive, profits were minimal. Large undertakings on the other hand not only defrayed the owner's expenses but also allowed him to invest further in his estate. The Glynnes of Hawarden, the Mostyns of Mostyn, and Edward Morgan are good examples of this. It would seem, however, that the pit owners, unless well-established, came out second best in this respect. Those that gained most were the traders (generally city merchants), who more often than not held the pit owner and the consumer to ransom with shrewd and merciless buying and selling. In order to get the coal off their hands for a quick return of their invested capital, the owners sold cheaply to the traders; with the result that they in turn were in a position to demand high prices31. Not many Flintshire families made their fortunes from coalmining; lead was the county's gateway to wealth.

THE FLINTSHIRE MINES extended the length of the county, and supplied local needs as well as contributing to those of Chester and Ireland. Inland coalpits, those around Ewloe, were operated mainly for their owners, the workings being small. What little surplus coal was produced from this source found its way to Chester by means of small barges by way of Wepre Pool, or by pack-mules and carts across Saltney Marsh. This trade carried on even when the city was under siege during the Civil War32.

The war was brought to Deeside because most of the gentry of the county were royalists; particularly so the Mostyn family. This had an adverse effect on the production of coal, and practically nothing is heard of the Mostyn collieries between 1640 and the Restoration. It was the same story in other parts of the county. The leases for coalmining in the lordships of Hawarden, Hope and Mold, had been in the hands of the Stanleys of Hawarden, and later of Robert Coytmor of Caernarvonshire, prior to 1640. In that year they were granted to Evan Edwards of Rhual and John Eaton of Leeswood.33 Edwards, if not Eaton, sided with the King, and the partnership was dissolved and the mines compounded by Parliament. In 1651-2 we discover Cotymor, a firm Cromwellian, once again in possession and complaining that the mines had been destroyed by the enemy, depriving him of his profits 'for the last five years'34.

The mines in the lordship of Mold were said to have been at 'Nannt Mauer', which is obviously Nant Mawr in the township of Bistre35. Surveys of the parish of Mold made in 1652-3, however, make no mention of coalworks;36 and we can probably assume that they were not worked again until Coytmor paid for them in the June of 1657.37

A close look at coalmining in the inland district centered around Ewloe shows continued activity throughout the seventeenth century. In 1619, for instance, Sir John Hanmer had interests in a mine at Northop38, while Robert Griffith owned one at Colepitt Hills in Aston39. Others were engaged in similar small enterprises in the townships of Bannel and Pentre-hobin (sic) by 1632; while Griffith ap Robert and seven, colleagues sank pits at Sychdvn40.

A group of high-ranking Englishmen in the service of James 1 held the Crown's manor of Ewloe lease at the onset, it passing in 1622 into the hands of Sir John North, who was described as a Gentleman Usher of the Prince of Wales's Privy Chamber.41 In the same year several of the tenants of the manor were brought to the courts for land encroachments, but the cases against them had to he dismissed because they could not be proven, as 'the metes and bounds are not certain' .42 North wasted little time in rectifying this by having the manor surveyed ;43 as the exact location of the lands of each tenant was now of prime importance, compared with the previous century when the privilege of working coal on their lands had been denied them.44 In an effort. to minimise any disputes he formulated a somewhat unorthodox solution by having the boundaries modified, arranging for some thirty freeholders to have parts of the demesne lands. In return they gave up their rights to some of the commons.45 There may have been more to this than meets the eye, for the best and most accessible seams lay under the common land, as, for example, at Buckley. Be that as it may, by 1625 it was revealed that the main coal mines there had "been improved since the makinge of the Extent"46. Another report about the same time gave a comprehensive list of those who dug coal at Ewloe. Yet, in spite of these precautions, in 1627 some of the tenants were accused of encroaching once more!47

In 1631, twenty-two years before its expiry, the assigned lease was transferred to Thomas Davies of Gwysaney. This family became Lords of the Manor and held the coal lease for the rest of the century.

AT THE ONSET OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY it was only the population living close to the mines who derived the benefit of coal fires on their hearths. Even the poor could be included here. In 1639, for instance, a woman appeared before the Great Sessions at Flint accused of having walked into a house in that town, and, picking up a piece of coal, "broke the face of Thomas ap Hugh of Attiscross."48 Later the use of coal began to spread to areas outside the neighbourhood of the mines, transport, more often than not, being undertaken by farmers with their carts.

Whilst journeying through the county, Celia Fiennes noted that the roads were "unsafe because of the coale pits" being in places "deep enough to swallow up a coach or waggon"49. Indeed, as early as the 1650's , the highway from the coalpits of Mostyn towards Denbigh was described as being in a deplorable state, and the bridge over Saltney marsh was out of repair.50

Edward Lloyd's observations at the close of the century reveal that coal had become universally adopted as domestic fuel throughout Flintshire, the few exceptions being the uplands, where peat and turf were still preferred. The main pits were still at Mostyn and along the Dee coastal strip, but supplies were also available from many other places, including Nant Mawr (Buckley) and Hawarden, where it was said that there was "Good store of coal in several men's lands".51 A Samuel Buxton was paying 17s.-6d. year "for ye Coalworke" at Bistre,52 and they were "sinking new Coal-pits in the Township of Leeswood"53. Workings were newly established also at Flint and Holywell. Those at Flint were on a common there called Maes-y-Dre, whilst twenty houses known as Pentre Pwll Glo (Coalpit Village) had appeared at one end of Holywell54. Extensive workings at Aston were the main suppliers for Chester.55

Coal was now being used in the salt industry after the Introduction of iron pans. Four Chester men had salt pits, a salt-house and pier erected at Morfa Afon Llwyfen near Flint in order to eliminate transport costs.57 Between 1698 and 1700 another gentleman by the name of Daniel Peck had a salthouse in the area as well.58

THE MEANS BY WHICH lead could be smelted by coal was still undiscovered. In 1693 the most advanced smelt in the county used charcoal,59 and five years later Lloyd noted that the position was unchanged: 'a Siarcol glo y maent yn krasu ei--- Bri'g'.60 Soon afterwards though Daniel Peck was experimenting with a reverberatory furnace for smelting lead with coal.61 Although his smelt was not altogether a success, it was the most important advancement yet. It was not, however, until 1704, when the London Lead Company erected a new smelt at Gadlys near Bagillt, that the first real breakthrough came about.62

Similarly, the first successful forging of iron with coal did not take place in the county until the Folly Group set themselves up at Bodfari in 1707.6

APPENDIX A. REFERENCES

1. Acts of the Privy Council (1547-50), p.545; also Chester City Records Office, ML/1/4.

2. Recs. Soc. Lancs. & Cheshire, Vol.111 (1969), pp.74-6.

3. Longfield, 'Anglo Irish Trade in the 16th Century', p.170

4. P.R.O., State Papers Domestic, (1547 -80), p.269.

5. Maddocks, 'History of Flintshire' (1949), Part 9.

6. Journal of Economic & Business History (1926), No.1. p.37.

7. P.R.O. State Papers Domestic, (1566-79), Addenda, p.441.

8. Nef, 'Rise of the British Coal Industry', Vol. I , p.53.

9. N.L.W. Bettisfield Mss. 1500.

10. U.C.N.W. Mostyn B. 9635-6; P.R.0. Mostyn (Hawarden) uncat.

11. Prec. Gen. Wales in temp. James 1, 149/35/1 ; 149/33/2

12. P.R.O. E. 178 / 3648/ 3.

13. N.L.W. Bettisfield Mss. 771.

14. P.R.O. E.178/3648/3.

15. P.R.O. Mostyn (Talacre), 94.

16. N.L.W. Wales 4/980/8/ -.

17. N.L.W. County List Manorial Records (Brere & Cholmely), p130

18. U.C.N.W. Gwysaney, Vol.2, 557

19. N.L.W. Bettisfield, 750

20. Bevan-Evans, 'Early Flintshire Industries', p11

21. P.R.O. E 178/3648/3.

22. N.L.W. Leeswood Hall, 587

23. N.L.W. Bettisfiels Mss. 323, 707, 1731.

24. Galloway, 'Annals of British Coalmining' (1898), p.219.

25. F.R.O. Mostyn (Talacre), 428.

26. N.L.W. (Brere & Cholmely), 150.

27. N.L.W. Calendar of Coleman deeds, 1244.

28. F.R.O. Mostyn (Talacre), 97.

29. Galloway, 'History of Coalmining in Great Britain' (1969), reprint p32.

30. P.R.O. E 179/221/230 in Cymm. Trans., (1959), p.105.

31. Nef, 'Dominance of the Trader in the English Coal Industry in the Seventeenth Century', Journal of Economic and Business History, Vol.1 No.3 pp 422-33, (Chicago 1929).

32. Flints. Hist. Soc. Pub. Vol.17, p.44.

33. N.L.W. Rhual Ms. 304.

34. Cal. Committee Compounding: Domestic Part 2, p.1113.

35. Royalist Composition Papers, Vol.2 C-F, ed. Stanning (Rec. Sec. 1892). Fe. 573.

36. F.R.O. D/KK/263: N.L.W. 4498 E/1.

37. Bevan-Evans, 'Mold and Moldsdale' (1949), Vol.1, p.79.

38. N.L.W. Bettisfield Ms. 1571.

39. N.L.W. Hawarden DD.221; N.L.W. Cwrt. Mawr Mas.673, 701.

40. N.L.W. Wales 4/930/8/~.

41. U.C.N.W. Gwysaney, Vol.1, 167.

42. Excheq. Proc. Cen. Wales, James 1; P.R.O. Decrees & Orders E 124/ 35/ 8 & 74.

43. Royal Commission of Hist. Mss. Sixth Rept. (1877) p.424.

44. Buckley, No. 2.

45. P.R.O. E 126/3 and Nef, Vol.1, p.317.

46. N.L.W. 9060 E.

47. U.C.N.W. Gwysaney, Vol.1, 169.

48. N.L.W. Wales 4/982/6/ -.

49. Colin Fiennes, 'Journeys' (1698), ed. Morris (1949), pp.181-3

50. N.L.W. Wales 4/984/3 & 5.

51. Edward Lluyd, 'Parochialia' (1698), Part 2, p.95 . One of the lessees in Hawarden in 1694 was Lawrence Walsh, Chester City R.O. C/Mc/46.

52. N.l.W. 4998 E/2.

53. Gibson, ed. 'Camden's Britannia', p.691.

54. Edward Lluyd, 'Parochialia', Part 1, pp.72-3.

55. Yarranten, @England's Improvements &c.' (1677), p.192

56. Afon Llwyfan was the old name for Nant y Fflint. See Ensau Afonydd a Nantydd Cymru' (R.J.Thomas), p.121.

57. House of Commons Journal (1698), Vol.12, p.301, Quoted in Trans. Hist. Soc. Of Lancs & Cheshire (1962), Vol. 114, p.104; Edward Lluyd ' Parochialia', Part 2, p.86.

58. Trans. Hist. Soc. Lancs & Cheshire, Vol. 114. pp.98-128. Peck was at one time Deputy Receiver of Lands for the Crown in North Wales and was also concerned with the Flints. Lead industry.

59. F.R.O. Mostyn (Talacre), 95.

60. Edward Lluyd, 'Parochialia'. Part 2. p.59.

61. Ibid. Part 1, p.83.

62. Flints. Hist. soc. Pub. Vol. 18, p.95

63. Economic History Review, Vol. 4 (1952), p.334.

APPENDIX B.

A survey of the Manor of Ewloe made during the reign of James I gives a list of 'The names of such as digge Colles in Ewloe in what grounds and under whome they digge'. It is to be found in N.L.W. Ms. 466/m.9 (Cal of Wynn of Gwydir Papers, 1308A. Dated somewhere between 1614 and 1625.

Mr Thomas Whitley of Aston

William TurnerIn the Hellynes under Mr Rich's

Nicholas Turner1beinge the lands of Mr Robert

Edward Ravenscroft2Stanley Esq.5

Will's Dymeg3

Robert Rosengrave4

Quere

Whether any be diggedJohn Sawthwork in the lands of Thomas

In the other groundsLedsham the younger, Coles have been

Of Mr Stanleysdigged of late in Shotton w'thin the

Lordship of Ewloe in Thomas Spark7 his lands.

There is not nor hath not of late any rent bene payed to the King's Ma'tie or to the Prince his highness for the said Collomynes.

Daniel Whitley8 payeth p.ann iij a. for Coles new digged in his grounds held by him there in Ewloe.

And Allexander Standish payeth vjs. P.a,, and no Colles digged in that lands, therefore it is to be inquired whether the said Pant be dew for the lands or for Collomynes.

And note there is a p'cell of ground held by Standishe beingse of a good quantity where it appeareth Colles have bene. Anntiently digged w'ch lyeth at the sowth syde of Ewlow. And likewise that of Sparke at the Northe s'de of Ewlow so that these seeme to be the anncient and not the depe works.

More payed for acore of the Englisshe side

John 'Messae9 iiij d

John ap Robert iiij d

Edward Fox did receive the ix s. above mentioned of Mr Whitley and Mr Standishe for Colomynes and iiij s. out of lands now Mr Ell' Ravenscroft for Colomynes, so received when he was bail', p.Ann.

(Note) if the vj s. by Standish be for the lands then there is but xij d short of the rent of the 560 Acres besides the decayes and the respit.

References: 1. of Breadlane 2. of Bretton Hall 3. of Chester 4. of Chester 5. of Hawarden 6. of Wepre hall 7. of Aston

Author: Gruffydd, Ken Lloyd

Tags

Year = 1975

Month = July

Document = Map

Landscape = Industrial

Work = Mining

Extra = Pre 1900

Copyright © 2015 The Buckley Society