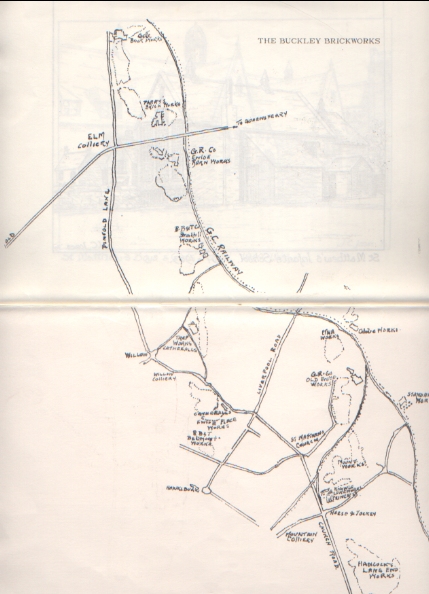

Buckley Society Magazine Issue One: The Buckley Clay Industries by George Lewis: map of Buckley Brickworks"

July 1970

Buckley Society Magazine Issue One, July 1970

This article covers the development of the potteries and brickworks, whose names in the text have been highlighted to facilitate searching. Buckley Foundry is mentioned at the end of the article.

See 91.2 for a photo of George Lewis and more information on him. He is the son of George Lewis, 1878 - 1963, whose diaries appear in entries 91.3, 4, 6 and 7.

THE BUCKLEY CLAY INDUSTRIES

BUCKLEY is well known in many parts of the British Isles and in countries abroad by the products of the valuable clay beds in the district. In earlier centuries it lay partly in Ewloe in the lordship and parish of Hawarden and partly within the manor and parish of Mold, the boundary being the ditch which runs from Lane End along the Hawkesbury Road to join the brook at Alltami. Its population was sparse and the people lived in the small townships which lay on the slopes of the high ground of Buckley Mountain - places known as Ewloe Town, Ewloe Wood, Pentrobin, Bannel, Argoed and Bistre. Not much is recorded of those early days, but we know that pottery and coal-mining were carried on within the Manor of Ewloe in the Middle Ages, and it is quite likely that these industries were within the Buckley area. The earliest firm reference to the making of pottery in Ewloe which has come to light is from the year 1435, and I would suggest that the Potterfield mentioned in this record might well have been the field adjoining Catherall's old brickworks which has always been called the Clayfield.

Buckley really begins its separate history in the eighteenth century when the important new channel of the River Dee was made in 1737. In the next twenty or thirty years rapid growth took place in the pottery industry. The ware was conveyed to the river at the ferry, then called King's Ferry, by horse and cart for shipment by small vessels to the ports of Wales and Ireland. Later on a narrow gauge tramway was made along which small, horse-drawn waggons were taken to the river.

The development of Buckley is a consequence of the clay and coal deposits found there. The potteries were supplied by the boulder clay which covers the whole area (ranging from two to fifteen feet thick) and which was deposited by glacial ice; and the brickworks are supplied by the fireclay beds formed between the outcrop on the Western Fault and the Great Fireclay Fault in the east.

Although Mr J.E. Messham has described the pottery making very fully, my purpose is to describe the industry as I remember it and as I learned of it from the previous generation. I remember six potteries working, as follows: Hayes's, near St Matthew's Church; Lamb's, adjoining St. Matthew's Infants School in Church Road; Wilson's, in a field below theTrap; Powell's, in Pottery Lane near the Willow; Taylor's at Alltami; and Gerrard's at Ewloe Green. All produced earthenware pots of various kinds and flower-pots. Chimney-pots were made by some potteries.

The process of manufacture was similar in all cases, and I think little change has been made from the earliest beginnings of the industry in the method used, except that, near the end of the working life of the potteries, machinery such as a pug or extrusion machine was introduced for tempering, and in the case of Powell's pottery a press was installed for making small lead-glazed pots for use at Walkers Parker Lead Works in Chester.

Normally in the spring of the year the boulder clay was dug either from fields near the pottery or from Buckley Common and carted to ths pottery by horse and cart, which seemed to be the most suitable way of transport, as access to the place of excavation would be difficult in any other way. When the clay arrived at the pottery it was placed in a large heap; and from this heap it was transferred to the blunge, which was a trough with revolving paddles, and by the addition of water the clay was reduced to the constituency of cream, it was then passed on to a fine sieve or screen which extracted the limestone pebbles and other impurities from the clay and allowed the liquid to flow on into ponds approximately forty feet square, where it would settle and become solidified in the course of several months according to weather conditions. It was essential to extract the limestone present in most of the boulder clay, as together with other such stones or grit they would in the first place render it impossible for the potter or thrower to perform his work, and secondly the limestone would slake when burned and render the pot useless.

The depth of clay in the ponds would be two to three feet, and in winter many a boy has had his legs covered with a clay casing when sliding on the frozen clay ponds and the ice has broken under him. When the clay in the ponds was in a state to be removed it was then carted to the pottery and placed on the shed floor as a clay bed about six feet square, to which water was added and trampled in by the feet until it was suitable for the potter to use. This was known as tempering, and was, as mentioned above, replaced by the extrusion machine at a later period. As the quantity tempered was greater than could be used immediately, it was covered with wet bags in order to keep it for the next day, and the clay that was not used was re-tempered with the next batch of clay. From there it was taken by the passer who was the person who weighed and handed the clay (in the correct quantity for the article to be shaped) to the potter, and afterwards carried the pot from the potter's wheel and placed it on a board to dry in readiness for glazing before being placed in the kiln. Any flaws which might appear in the pot being dried were attended to by the fettler, who also glazed what was necessary by pouring a quantity of slip lead or other glaze mixture into the pot, whisking it round, and pouring out the residue into the vessel which held the glaze. In order to place the ware in the kiln, kiln furniture known as saggars had to be used to enable the pots to be held firmly by the rim to the full height of the kiln, which contained approximately nine tons of pots. The burning took at some works forty eight hours, and at others sixty hours, where a smoking or further drying period was employed at the beginning. The labour force in each pottery was very small and the potteries were often run by one family who were the owners.

Whether or not geological information was available, I would suggest that the fireclay and coal in Buckley were discovered by the outcrops which occur, and it is reasonable to assume that the first firebrick works, started by Jonathan Catherall "soon after the making of the Dee channel" (where the present Catherall works is situated and where he had previously had potteries), was a direct outcome of pottery making. He no doubt found the fireclay at the base of the boulder clay which he had dug up for pot making, and possibly had tried to fire it and had discovered that much greater heat was required and that it had fire-resisting qualities suitable for brickmaking. The fireclay beds in Buckley extend from Lane End to Castle Old Works claypit, and in some places are a thousand yards wide. The Geological Survey says that the Buckley Fireclay Group is the top member of the middle coal measures but that no such beds of fireclay are known in any other middle coal measures of other coal fields.

These remarkable beds of fireclay were used by about a dozen works founded in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In Lane End was Hancock's, after Catherall's the oldest of the Buckley brickworks. Other brickworks were Prince's (on Church Road), the Mount (on Knowle Lane), the Old Ewloe or Davison's Top (near St Matthew's Church), Etna (adjoining Old Ewloe), the Buckley Brick and Tile (at Brookhill), the same firm's works at Belmont, Catherall's at Ewloe Place and (the old works) below the Trap, Ewloe Barn or Davidson's Bottom works, Edward Parry and Sons Ltd. (near the Elm Colliery) and Castle Brick. The Castle Fire Brick Company Ltd. was begun in 1865 by G.H. Alletson and others. All these works began clay getting on the outcrop of the Western Fault. I can remember all of them operating, a fact which illustrates the extent of the fireclay industry at one time.

The works known as Prince's, the Mount, Etna, Belmont and the Trap, have long since ceased to operate and their clay pits have either become water-logged or have been filled in with refuse. Brookhill, Catherall's , Hancock's and Parry's are now owned by the Castle Brick Company, Ltd. and this company was taken over by Messrs John Summers and Sons, Ltd. in 1916. The works at Old Ewloe and Ewloe Barn are owned and operated by General Refractories of Sheffield. I should also mention another works which I remember (now demolished) known as the New Mount at which there was a very fine chimney. The locals called it the Sugar Stick because it had spirals of white bricks built into it from top to bottom, and also had a very large oversailing coping. This chimney was certainly a landmark and could be seen from a very long distance away. I do not remember this works operating, and I understand from older people than myself that it only worked for a very short time; one explanation for this being that there was no fireclay to be found in the small claypit opened by the works. I can now say that this explanation was wrong, as I have recently been connected with diamond core drilling at this particular point and have found the fireclay beds back to the Great Fireclay Fault similar to any other claypits in the area.

The fireclays have all been worked by opencast method from the outcrop which falls North East, and after many years of working the full formation can be seen at the faces in most pits especially at Lane End pit. This pit has now disclosed the South end of the Great Fireclay Fault. At the surface in this pit the drift boulder clay and gravel deposited during the glacial period is of considerable thickness. The Knowl Hill forms part of it; it is mainly sand and gravel with a clay content which unfortunately renders the gravel unusable for building purposes. Below this is sandstone rock formed by sand deposit, and next comes the Carboniferous fireclay beds which were laid down long before the upper strata. These Carboniferous clays are composed of the Buckley Blue fireclay averaging approximately fifteen feet thick. Below is a black clay up to seventeen feet thick. This is usually followed by a very thin coal seam of no commercial value, and afterwards by a grey and red 'warrant' fireclay which has not been worked anywhere extensively as it, in most cases, possesses ironstone nodules which make it costly to use unless special separating machinery is installed.

In the pit at the Buckley Brick and Tile works at Brookhill another seam of clay can be seen between the blue clay and the black clay previously mentioned. Thus there are here two blue clays separated by a band of white rock approximately two feet thick. This lower blue clay is less refractory and will not resist as much fire as the upper seam, and consequently vitrifies at a lower temperature, making the material less porous and glassy and therefore able to be used for fire and acid resisting purposes. Both the upper and lower seams of blue clay are manufactured into bricks and shapes of all kinds to suit customers' requirements for use in furnaces etc. and in chemical plants where abrasion and resistance to thermal shock is important. The black clay is extensively used where greater heat resistance is required as for example, in the making of ladle bricks for lining steel ladles into which molten metal is poured.

Before explaining something of the history of the manufacturing processes, I should say that the reserves of fireclay and rock, extracted at the rate of two thousand tons a week, as at present, for the manufacture of fireclay goods and facing bricks for building, will last for many years. This has been recently proved by the diamond core drilling already mentioned.

The winning of clay in the early years of the industry was most certainly done by hand, and no doubt the clay was brought to the preparation shed by horse and cart and eventually by haulage-winch in small tubs on a narrow gauge line. This method was employed, driven by steam or electricity, until the 1930s in some pits, and in others until quite recently. The winning of clay is now done by mechanical excavator, the overburden having been first removed by powerful bulldozers or mechanical diggers. Explosives have, as in the past, to be used to remove the rock above the clay, and I remember when shot-firing holes into which explosives are put had to be drilled by punching a hole by hand with a steel bar into the rock. The holes are now drilled mechanically. The clay is brought from the pit by motor lorry.

I have not seen any record of what machinery, if any, was originally used for crushing the mixture of fireclay and rock, but for very many years this has been done by crushing rollers, the clay passing through them in flake form into a circular trough in the floor of the shed called 'the treading'. Water was then added and the whole mass was mixed by a spiked rotating arm called 'the horse' . This name probably came from the fact that it was originally pulled round and round by a horse, but when I knew the process it was mechanically operated by a steam engine. The water penetrated through the clay, soaking it and making it suitable for moulding into bricks and shapes - the clay being selected by the moulder from different places in the trough where he learned it was in the best condition for the particular article he was going to make. The method of digging out was the use of a steel paddle, the clay being loaded onto a barrow and wheeled to the moulding shed. The amount of clay taken out each day varied by the size and number of things to be made. It was, in the case of the brick moulder, about eight to nine tons, out of which he made 1,750 to 2,000 bricks a day. The bricks were put on a warm floor for drying by a boy of often not more than fourteen years of age, who usually worked in bare feet. The size of these bricks was 9" x 4 1/2" x. 3" and 9" x 4" x 2 1/2". They were moulded in a wooden mould with no bottom to it, on a bench. The boy had to learn how to take the brick off the bench without letting it drop out of the mould before placing it on the floor to dry. As can be imagined, this number of bricks covered a fairly large floor space, and in order to obtain sufficient room for the next day's 'make' man and boy would return to the works in the evening after their meal to pick up the dried bricks and stack them into a wall at the side of the shed. From here they would be loaded onto a specially shaped barrow with no sides to it, and taken to the kiln by the kiln setter. This method of brick moulding ceased in the late 1930s, with the introduction of mechanically operated presses. From these presses the bricks come with much less water content and can be handled easily without being damaged, and they are taken directly from the machine by fork-lift truck to tunnel dryers which are used instead of the warm floors.

The preparation of the clay is now done by passing the clay through perforated grinding pans in dry form, and afterwards tempering it in single or double shaft mixers, where water is added. From this mixer the clay is passed either into the pug of the press for making pressed bricks, or to the pug to be extruded and cut into size by wires as the extruded column passes along the cutting off table - these bricks are called wirecut bricks. Hand moulding of shapes is done in the same way as it has been done for many years, indeed, for far longer than I remember and I regard the moulders as craftsmen. The type of material to be seen on the drying shed floor will be evidence of their skill. Buckley Brick and Tile, especially, were experts in intricate moulding through the skill of a very clever moulder, Samuel Fennah of Liverpool Road.

I have often wondered what the first Jonathan Catherall did to burn the first bricks he made from fireclay, as the pottery kilns would not stand up to the temperature necessary. I venture to suggest, however, that the bricks could have been placed in the pottery kiln and burned as hard as possible and the very hard ones selected to build the inner casing of the firebrick kiln (the

outside wall bricks could be made of potters clay, burned slightly harder than pots); these would have lasted until the firebricks, burned properly, could be produced. But as I have no record of what was done, your guess is as good as mine. He could, however, have used the old clamp kiln method, which consists of two side walls into which the bricks and coal are placed in the hope that the amount of coal used would burn the bricks sufficiently for building a firebrick kiln. In passing I might mention that the walls of the clamp kiln used to provide bricks to build the works at the Castle brickworks in 1865 now form walls of a narrow drying shed at the Old Works.

The firebricks are burned today in the 'beehive' down-draught kiln, which has been used from very early times,and is, however, either under oxidising or reducing conditions to suit the product required.

The drying sheds at Catherall's works were built of stone, which indicates the shortage of bricks; and quite recently, in order to carry out improvements, these walls were taken down and an excellent example of wattle and daub was found.

Materials made from Buckley fireclays are sent to many places in this country and abroad. I regret that the very large Irish business for flooring tiles, ridges and other large size tiles and bearers, which existed for many years, has lately become very much reduced, because of the use of concrete. It will be of interest to know that the bricks for lining the railway tunnel from Birkenhead to Liverpool came from Buckley. This very useful order kept all the works in Buckley busy at the time, as the bricks were hand moulded. Lord Street in Southport is paved with 9" flooring tiles - all made in Buckley.

During the war a soldier from Northop Hall was in the Middle East and picked up a brick stamped with the word 'Northop', which was a trade-mark of Castle Brick Company, who supplied these bricks for kiln building. The builder was William Jones & Sons, of Liverpool Road, Buckley. Firebricks are now being supplied by Castle Brick Company for lining a chimney 650 feet high with four separate flues at Fawley, Southampton. I must at this point mention the very important contribution which Buckley has made in providing facing and common bricks for the erection of houses, schools and public buildings, not only in Flintshire, but in other counties in England and Wales. Sales of building bricks have often been over thirty million bricks in a year. Buckley has also provided glazed pipes made by the Standard Brick Company.

In the early days, and well on into the present century, horses and carts were the main means of transport to fetch coal from the colliery or from Knowle Lane railway siding in Church Road (to works where no siding connection to the railway was possible) or to carry goods to the river (in the early days) or the railway (more recently). Catherall's and Hancock's works had their own very fine teams of horses. Both works sent goods by rail, but having no railway sidings in the works, they sent their goods in small trucks drawn by horses along narrow gauge tramways to join the railway, where the goods were transferred to railway waggons. For shipment at Connah's Quay each works owned its own railway trucks, called 'shippers'.These trucks had only ends and no sides, and were fitted with tramway lines of the same gauge as the tramway along ,which the horses brought the goods in the small, sideless trucks, known as shipping boxes which were pushed straight onto the railway trucks, instead of having to be unloaded. At the four top corners of the ends of the shipping boxes were four eyelets into which sling hooks could be fixed, and the box was then lifted and lowered into the hold of the vessel to be unloaded by men sent from the brickworks (known as shippers or stowers) who knew how to stack the bricks correctly in the ship. Where horses were employed, blacksmiths and wheelwrights were necessary, and Buckley had at least four smithies in my recollection. These were at the Willow, in Liverpool Road, at Buckley Square and Daisy Hill. Collieries kept their own blacksmiths for shoeing, as numerous pit ponies were used in the mines, but the blacksmiths at the brickworks were employed more for machine maintenance than for shoeing horses. Machinery was attended to by Buckley Foundry in Brunswick Road both for repairs and renewals. The ancient smelting tower at this foundry, which was very recently demolished, was perhaps the last remaining memorial to bygone methods in the industries of Buckley.

Author: Lewis, George

Tags

Year = 1970

Month = July

Building = Industrial

Document = Journal

Landscape = Industrial

Transport = Rail

Work = Heavy Industry

Extra = Pre 1900

Copyright © 2015 The Buckley Society