Buckley Society Magazine Issue One: Medieval Coalmining in Flintshire by Ken Lloyd Gruffydd; map of Manor of Ewloe"

Ewloe Manor

July 1970

Buckley Society Magazine Issue One, July 1970

Medieval Coalmining in Flintshire:

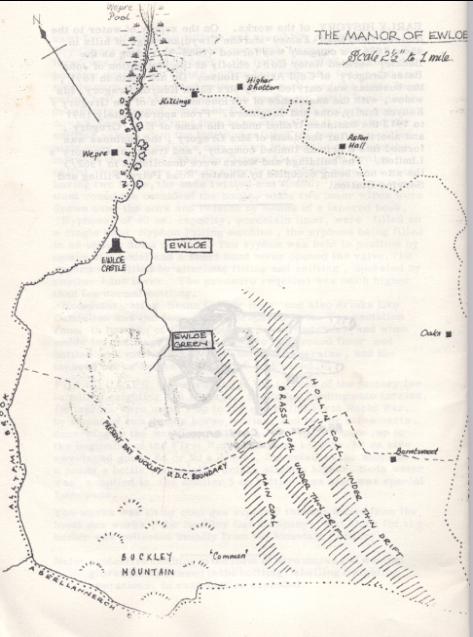

Map of Ewloe Manor to illustrate article

Scale 2 1/2" to 1 mile

see 79.4 for illustration

MEDIEVAL COALMINING IN FLINTSHIRE

WHEN EDWARD I undertook the conquest of North Wales in 1277 he lost no time in securing his hold over the lands between the Dee and the Clwyd, and immediately began the building of the castles and towns of Flint and Rhuddlan. Labour for this formidable task was brought in from England but the materials were obtained largely within the confines of our present-day Flintshire. Stones for the masonry work were quarried from local limestone and the lead for roofing retrieved from the ancient mines at Holywell and Halkyn. Iron ore for the forges came from small outcrops in the forest of Rusty (Yr Estyn in Hopedale) and Ewloe; so also the wood for timbering. Between 1279 and 1284 we have on record coal (1) being taken from Holston (near Bagillt) to the smithy at Flint castle, and by 1294 it was being dug at Mostyn.(2) An extent or rental of the Manor of Ewloe dated 1295 makes no mention of coalmines there, but at the beginning of the following century the most important source was without doubt the Buckley-Ewloe district. Here were outcrops of Main and Hollin coals very close to the surface. The seams each about six feet in thickness, covered an area roughly half a mile wide, and extended for about a mile in length.

A couple of points must be borne in mind though, before we deal with coalmining in the Buckley area in Medieval times. Firstly, it must be realised that during this period there was no settlement at Buckley - it was the pasturage or grazing-land of the manor of Ewloe. Its location as such was probably what we know today as the 'Mountain' and the adjoining 'Common'. References to mining in the district, therefore, invariably come under Ewloe, but as the coal outcrops occur between present-day Ewloe and Ewloe Green on the one hand, and Buckley on the other, there is little doubt that some of the medieval mines were within the area of Buckley as we know it. In actual fact the earliest reference, in 1312, specifically mentions the Forester of Ewloe Woods paying the rent for "the pasture of Buckley and for the sea-coals therein." (3) The other point to remember is that coal at this time was referred to as 'sea-coal' as distinct from 'coal' which was the name used to describe charcoal. The reason for the adoption of this name for coal is not clear. It might have been due to the fact that coal was found on some of the sea shores of Britain, (4) or because it was frequently transported by water.

When the county of Flint was created in 1284 licences for mining within it were granted by the Earl of Chester (to which earldom the new county was added), the earldom being held by the Crown or by the heir to the throne (that is, after1301, when Edward, son of Edward I, was created Prince of Wales, by that Prince). The right to the minerals within the Manor of Ewloe subsequently belonged solely to the earl and even the free tenants had to surrender any coal dug on their lands without licence or pay a corresponding royalty in lieu of same. Those who were fortunate enough to be granted licences could only use the coal for their own domestic purposes, and in no way were they allowed to sell it. (5)

During the early years of the fourteenth century the only person to be granted such a licence in our area was a Welshman named Bleddyn (Fach) ap Ithel Annwyl. His son Ithel later enjoyed the same privilege; both paying the lord 53s. 4d annual rent. (6) In 1347 Bleddyn lost the family lands to the Prince (as earl of Chester). This may have been as a result of "divers destructions" done to Ewloe Woods in the previous year. (7) Bleddyn was Forester at the time and the responsibility for the protection of the woods lay with him. As an alternative, the mines may have been located within the woods and the exploitation of new workings could have resulted in "trespassing" and damage being done. Bleddyn was, however, allowed to continue working the mines at the old rent. Later on in the century we find that the lands had been returned to the descendants of the original tenants. In 1389, for instance, the heirs of Ithel ap Bleddyn ap Ithel were described as having the lease of coals "held of the King on their own soil."(8) Indeed, Ithel himself might have retrieved them as early as 1358 for in that year he was granted letters patent of the same "for as long as there be a coalmine there." (9) He had been made escheator of Flintshire in December of the previous year and this could well account for it. He was notorious for the malpractice of the powers entrusted to him . The last mention of the heirs of Ithel ap Bleddyn ap Ithel occurs in the Recognizance Rolls of the Earldom of Chester for the year 1408. (10) After this the mines may have been exhausted, or included with others of the manor under a single lease.

The sea-coals within the Prince's demesne lands, together with those under the lands of other free tenants of the Menor, were leased out to the Forester of Ewloe Woods as part of his 'farm'. Cadwgan ap Ithel held this office in 1312 paying £7-6-8d for it. An entry in the accounts of the Chamberlain of Chester for that year showed that he was in arrears with his rent; this confirming the existence of the occupation and its associated responsibilities prior to that date. (11) In 1322 the previously mentioned Bleddyn acquired the lease of the forest, mills, "pasture of Bokelegh', coamines etc. (12) This meant that he now worked all the coals within the manor; but this situation was to change in 1331 when a group of Cheshire men took over the 'farm' for three years at an annual rent of £8. (13) Prominent amongst these Englishmen wore members of the de Praers family. Robert, the eldest, became Sheriff of Cheshire in the following year and Richard held the same post for Flintshire in 1336. The third member was William. (14)

It had become common practice at this time for outsiders to speculate and invest in Flintshire's mineral resources and particularly so in the more profitable business of lead-mining and its bi-product, silver. It was soon realised though that the gains from coal were far less lucrative and by 1341 Bleddyn was once again sole lessee. (15) This position was unchanged in 1349 (16) but his sudden disappearance in the following year gives room to believe that he fell victim to the Black Death which took so many lives in the county at this time. Both leases were taken over by his son Ithel Fach who paid the sum of 106s-8d for them. (17) During this period the Forest of Ewloe had been partially destroyed. (18)

The year 1354 saw a change in the policy of the Earldom towards the leases within the Manor of Ewloe. From now on the coalmines were farmed out on a separate lease from that of the Forester; Ithel managed to keep possession of the coalmines. For the right to dig in his own lands he was to render the same sum as before, that is, 53s-4d (four marks), and for the same privilege on the lands of the lord and other tenants,80s (six marks). In 1364 he renewed the last-mentioned lease but relinquished it after a very short period; although he continued to hold the lease for the coals "on the land which (he) ...held of the Prince." We hear the last of Ithel in 1386 when he was said to be living in Weper (Gwepra) and when he was granted the king's protection on his departure for the coast where he was to remain for the defence of the realm . (19) There is a stone effigy of Ithel and his wife, Gwenhwyfer, in Northop Church. On it is the following inscription:

X HIC : IACET : ITH : VACH AP : BLED : VACH

That is, in English, " Here lies Ithel Fach son of Bleddyn Fach".

Mr Colin Gresham of Cricieth estimates the date of the effigy at about 1395 (20) but Ithel probably died before then; in 1387-8 perhaps. The family lands were in the hands of his 'heirs' in 1389 (21)

David de Ewloe is the name connected with the mines from the year 1365 to the year 1382. (22/23) He became mayor of Chester in 1381, a post he held for a further five years.

There are instances on record whereby the revenues from the Manor of Ewloe did not go to the Prince. Between 1320 and 1327 a portion of them had been granted to a certain Madoc Stulf; (24) and in 1366 to Thomas Payevyn, steward of the Princess's household, (25) both probably awarded for some services rendered. This last named gentleman was a non-resident, but nevertheless received a profitable income from the same, as can be seen in 1387 when William de Meysham of Ewloe paid £204 for the right to the 'farm' for six years. (26) Three years later, on the very day of Payevyn's death, William de Meysham began paying the king for the same privilege, "except for the coalmines." (27) For these he had to pay an extra £7 per annum. He held them in partnership with another local man named Robert Launcelyn, who had once filled the office of sheriff of Chester. From 1392 onwards William de Moysham was further granted an annuity for life of £4 to be received as issues from the farm of coals of Ewloe "in lieu of the custody of the park of Thloitcoit" (Llwydcoed, in Hopedale) (28) The documentary evidence relating to this particular partnership is somewhat complex and we can but conclude that all was not wel with them financially. This is perhaps substantiated when, in 1394, Ithel and Cona ap Kenwrig (Bleddyn Fach's grandsons) appeared on the scene, paying a recognisance of 40s in part payment of £7 of the farm of seacoals of Ewloe. (29) During the same year John de Ewloe became coparcener with William de Meysham in the 'farming' of the manor, and within two years the latter had surrendered his share to John. In actual fact John de Ewloe had been granted the lease of the sea-coals in 1395 for a period of six years. By now there were three mines within the manor. The conditions in the lease specifically stated that it pertained to "the coalmines of Ewloe" and was not to include those worked by the heirs of Ithel Fach on their own land, nor those held by John himself, which he had 'of inheritance'. This is corroborated in the grant of another lease in the same year giving John the right to sell the coal on his own estates. (30) We are not told what he received for his coal, but a 'chaldron' sold at Newcastle at this time fetched only 2s. (31) Within a matter of another three years John had gained permission to seek, work and sell sea- coals on part of the king's estates which he rented at 8d an acre. (32) The refreshing change in the Crown's attitude towards the mining and selling of coal during these last few years of the fourteenth century should be noted.

Difficulties arise when trying to ascertain the exact nature of the methods employed in the working of the mines. With the seams so near the surface the only procedure required in places would have been scraping away the covering of alluvial drift. For the deposits that dip downwards the characteristic method for the extraction of the coal was by means of bell-pits. The size of the pits depended largely on how deep the miner had to go before reaching coal. Very rarely did the work proceed deeper than ten feet as no attempt was made at any gallery-work, drainage or timber shuttering. The name 'bell-pit' was derived from the fact that the miner worked away all-round, leaving behind bell-shaped depressions. Once the pit was exhausted a new one was dug at about eight or ten feet distance, so that a familiar sight was a row of these shafts running in a straight line, following the main seam. There is a series of hump-like features at Burntwood which may have originally been medieval bell-pits now filled in. The place-name itself suggests an association with coal or charcoal, and may be compared with the Welsh name Coedpoeth. Great care was taken of the mines as is seen from an entry in the Recognizance Rolls of 1390, when the Crown instructed its Master Carpenter in the counties of Cheshire and Flint, to take one oak from the Ewloe Woods for the repair of one of the local workings. (33) The cost of sinking one shaft was relatively cheap: £3 in 1399. (34)

Most of the coal dug in the earlier days was taken to the local castles where it was used in the forges or in the burning of lime for building. Later it found its way to Chester where it was employed for domestic purposes and brewing as well as by craftsmen. The means of transportation at the onset was by way of land-routes. (35) Carriers operated carts and pack-mules across Saltney marsh. The terms for coal weights in the county were 'quarter', 'pytche 'and' chaldron'. The last two were slightly less than 2 1/2 cwts and approximately 27 cwts respectively. After 1326 we find coal reaching the city of Chester by way of the sea. (35a) At this time a boat-load or coal-barge was known as a 'keel' and comprised twenty chaldrons. However, in order to evade the 2d export duty merchants built keels of 22-23 chaldron burden. Various methods to combat this malpractice were unsuccessful, with the result that by the end of the Middle Ages the chaldron had nearly doubled its original weight, and was equal to two tons in weight. (36)

It is evident that by the 1380s, if not earlier, coal was also being worked at the Faenol in the extreme north-west of the county. This township belonged to the bishop of St Asaph and in 1397 the bishop was claiming the right to dig coal there as his predecessors had done. He had complained earlier that the king's ministers were depriving him of his revenue from this source, with the result that they had been ordered to "desist from hindering and grieving the bishop in taking the profit of mining lead, stone and coal upon his land. . ." (37)

There is little doubt that 'sea-coal' found its way into the most prosperous homes of Flintshire at this time but a reference made by the poet Iolo Goch, sometime during the second half of the fourteenth century, suggests that the local people preferred peat and wood for their fires. Describing the warm welcome he received at the bishop's palace at St Asaph, he commented that

even there :

Tan mawn a gawn, neu gynnud;

Ni bydd yno'r morlo mud (38)

('A fire of peat or wood is had; they use not the dumb-quiet burning?-sea-coal') .

For the first three years of the Glyndwr rising John de Ewloe managed to continue working the mines, but in 1403 the accounts of the Chamberlain of Chester reveal that there was no revenue from that source "because of the rebellion in the district". A point also to note was that the number of carriers of coal to the city of Chester had dwindled to only three; the reason being that they "dare not do so . . .by reason, of the war between the Welsh and the English in those parts". (39) It was not until 1408 that the lease was again taken out. (40) A generous effort to get mining going again is seen from the fact that the mines were let for the low rent of 5 marks (66s. 8d). This was to be for the first two years and the rent was to then increase to £4 a year for the remaining eight years of the contract. (41) We hear the last of the above John in 1434 when he was reported as being unable to pay debts owing on his 'farm' or lease. (42) He had held it for nearly forty years and must have been a figure of some prominence in his day. He once enjoyed the honour of being mayor of Chester (1404-10), although his term of office was brought to an ignominious end because of an alleged "want of loyalty and tampering with rebels." (43)

Richard Whitley took the lease of "the lordship, together with the coalmines" in 1437 for a period of seven years, but did not re-establish his claim to it at its termination; (44) possibly because of arrears on his account. (45) His name turns up later though in connection with the mortgaging of some private lands in Acton, Shotton, Hawarden and Ewloe, owned by David and Roger Costantyne. As part of the agreed rent Whitley was to render "a moiety of such coal" as he extracted from the said lands. (46) From now on we start to observe a gradual change in land disbursement. Individual tenancy was slowly creeping in and in the above agreement we witness the first instance, in relation to the mines of Ewloe, of a proportion of the coals dug being given as part payment of the rent. This became a common practice during later years, by both the Crown and private landowners. The amount of royalty was generally specified.

For six years after 1445 the mines were in the hands of a family called More. The members mentioned being Nicholas and Robert. Nicholas had been made steward of the township of Ewloe in the previous year and held the same post for Rhuddlan in 1445. In 1450 Robert, who seems to have been the son, became bailiff of the hundred of Eddisbury in Cheshire, and this may account for his relinquishing his share in the coal mines of Ewloe on the termination of the lease. In 1451 Nicholas took out the lease once more; this time his partner was one Thomas de Poole. They had to pay an additional 3s-4d on the old annual rent. (47)

In 1461 the lease came into the possession of the Stanleys of Hawarden. The first member of this famous family to hold it was Peter Stanley, who acquired it in the very year that his father, William, became sheriff of Flint. (48) Peter Stanley was reported to be in arrears with his rent within the demesne of Ewloe in 1474, (49) and it was about this time that his son Thomas took over. (50) The lease of the coalmines of the Manor of Ewloe (and therefore of Buckley) remained with the Stanleys for another hundred years.

Appendix of references in Article on Medieval Coalmining

I. Pipe Roll 131, m.26.

2.Rees. W., Industry before the Industrial Revolution, Vol.I.p.35.

3. Flints.Min.Accts.No3. 4. Salzman. L.F., English Industries in the Middle Ages, p.2.

5. G.M. Trevelyan, Illustrated English Social History, Vol.2. p47.

6. Flints.Mins. Accts.No.2

7. Exchequer Treasury Book No.144 p.12; Black Prince Reg. Part I , p. 15.

8. Deputy Keeper's Report, (36th) P.R.O. Appendix ii,p343. (hereafter referred to as

DKR)

9. Black Prince's Reg. Part 3, p. 368 10. DKR (36) p. 177.

11. Flints. Mins. Accts. No. 3 12. DKR(26) p.176. 13. ibid.p388.

14. High Sheriffs of Flints.(1300-1963), Breeze & Jones-Mortimer, p.7.

15. DKR(36) p.176. 16. Flints .Mins. Accts. No.2. 17.ibid.

18. Cat. MSS. Relating to Wales in the B.M.Part IV No. 4484(f); see Note 7.

19. DKR(36),p. 260. 20. C .Gresham, Medieval Stone Carvings in North Wales

(1968), p.54.

21. DKR (36) p.345. 22. ibid.p. 176.

23. Could he have been Ithel's son? A David ap Ithel Vach appears in the Black

Prince's Register (Part 3.p.80) in connection with the seizure of that family's

lands. David ap Ithel Vychan also appears in 1336-7, Mostyn (Bangor) MSS, DD.

2171 .

24. Flints. Mins. Accts. No 3. DKR (3b) p.176.

25-30. D.K.R. (36) pp.381, 176, 373, 176 (Talbot Deeds 99),40, 177.

31. Salzman, p.19. 32. DKR (36) p,177. 33. Ibid. p.343.

34. I.B.I.R. Vol. l. p. 115.

35. Morris, R.H. Chester during the Plantagenet and Tudor Periods, p.276.

35.a. H.J. Hewitt, Cheshire under the three Edwards, p. 47.

36. Saizman, p.18.

37. I.B.I.R. Vol.1.Introduction; W.J. Lewis, Lead Mining in Wales, p. 35.

38. Cywyddau lolo Goch ac Eraill (1350-1450), ed Roberts, Lewis,

Williams, p 84.

39. J.E. Messham, Glyndwr Rising in the County of Flint, F.H.S. Vol.23, p.13;

Chamberlain 's Accts. S.C.6/775/1.

40. DKR (36) p.177. 41 . ibid. 42. DKR(37) p.357.

43. DKR (36) p.104; Chester Freeman Rolls, Part I. p. 2.Morris .Chester, p. 47.

44. & 45. DKR (37) p 268, 343-4.

46. N.L.W. Cal.Coleman Deeds &' Docs. No.1153.

47. DKR (37) pp. 269, 551, 594.

48. Ibid. p.263. P.R.O. Lists and indexes No. IX , Sheriffs, p.254. I.B.I.R. VO .1. p. 72. 49. Moore Deed No. 1091 ; Lord Thomas Stanley took out the lease in 1472 for a rent

of £20. 10s.

50. DKR (37) p.270.

Author: Gruffydd, Ken Lloyd

Tags

Year = 1970

Month = July

Document = Journal

Landscape = Industrial

Work = Mining

Extra = Pre 1900

Copyright © 2015 The Buckley Society