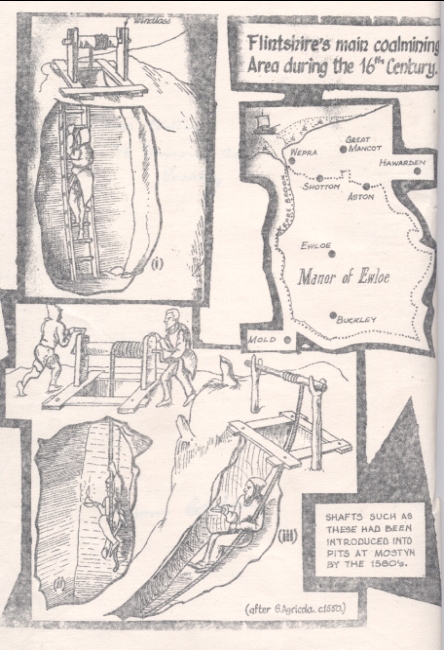

Buckley Society Magazine Issue Two: Coalmining in Flintshire in the Sixteenth Century by Ken Lloyd Grufydd: Article and Frontispiece; Flintshire Main Coalmining Area during the 16th Century"

Flintshire

July 1971

Buckley Society Magazine Issue Two, July 1971

COALMINING IN FLINTSHIRE IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY

DURING THE MIDDLE AGES coal had been spasmodically worked at five different locations in Flintshire, namely, at Mostyn, Hope, on episcopal lands near St Asaph, at Hawarden and at Ewloe. It was only at Mostyn and Ewloe however that production seems to have been uninterrupted throughout the period, the latter place being the chief coalmining area in North Wales.

A scarcity of detailed documentary evidence concerning coalmining during this time reflects perhaps a lack of interest in the early growth of the industry by both landowners and the Crown. Indeed one might go so far as to say that up to the end of the fifteenth century, that is, up to the Tudor period, coalmining in Flintshire, as in most other parts of Britain, was still thought of as being just another of the perquisites of the lord's demesne. Little notice was given to it as it contained no precious metals and brought in only a meagre revenue. Prior to the beginning of the fourteenth century it had more or loss been a winter occupation of those people generally associated with the cultivation of the land during the warmer months, the bondmen carting away from the pit only what the lord of the manor required for his hearths, lime kilns and smithy. Slowly though, as agriculture began to follow a more definite pattern of development, so also did the mining for coal become a minor, but separate, undertaking. One ought not perhaps to call it an industry as yet. By the beginning of the sixteenth century the manorial system as such had to a great extent broken up. No longer did it function as a unit in itself. But many customs remained unaltered. To obtain a clearer picture of the situation concerning coalmining one must realise that it was customary for the Crown or the lord of the manor to have undisputed right to the minerals within his lands. There were exceptions whereby freeholders and tenants were awarded certain reservations permitting them to dig for coal upon the lands which they held or giving them ready access to coal upon the common lands. In 1497 for instance Peter Stanley was given the right to have one man to hew coals in his own mine or coalpit at Ewloe, but, was only allowed to take away from it daily a measure called a 'scar of coles'. This was an obvious attempt at conserving the supplies of coal from premature exhaustion. The term 'scar' may be of local origin, resembling perhaps the English 'scope' or basket full. Other tenants, amongst them one Adam Birkhened, also took advantage of this privilege, paying for it an annual sum of four marks.(1)

The common lands of Ewloe were located in Buckley, and the inhabitants of the manor were permitted to exercise their rights within them but reference to their being allowed to work coal (as tenants were allowed to do at Brymbo in what is now Denbighshire) is lacking. They probably were not. But there are references to 'customary tenants' in the records of the manor, that is tenants enjoying special privileges by some long established tradition. Stemming from the Edwardian policy of making as little change as possible in existing Welsh customs, we find that in the fourteenth century one Ithel ap Bleddyn was allowed to mine coal on his own land,(2) no doubt continuing to enjoy a privilege granted to his ancestors by the Welsh prince, Llywelyn

ap Gruffydd. This 'liberty' was continued in his descendants for over a century, but may have been terminated in 1500 when David ap Rhys Wyn ap Dai ap Ithel granted part of his lands in fee-simple to a John le Stryt. The coalmines therein were described as being located 'near the road leading to Bukley.' (3) At the end of the fourteenth century a John de Ewloe was allowed

to dig upon land which he had 'of inheritance' but he did not remain a true 'customary tenant' for long, as he later sold it.(4) In 1528, John Both, Archdeacon of Hereford, also claimed his rights to mines he had in Ewloe, ones he referred to as 'the inheritants of your said subject.' This was the last reference to any kind of special concession regarding coalmining within the manor.(5)

THE CROWN FARM and major coalmines of Ewloe were in the hands of the Stanleys of Hawarden castle from the middle of the fifteenth century;(6) the lease being renewed from time to time. It will be noticed that the earlier leases were for relatively short periods, as is seen from the one taken out by Peter Stanley in 1509-10, when he acquired it for four years at an annual rent of £20-l0s.(7) A greater demand for coal and a consequent rise in its price, altered this practice, and in 1535 Peter Stanley, Jnr., 'one of the gentlemen ushers of the King's Chamber' secured a renewal of the lease for forty years.(8)

It is evident from a dispute that arose sometime between 1553 and 1558 that the lord of the manor had realised the potential exploitation of coal and had adopted a policy of refusing the freeholders of the manor licence to dig for it; thus keeping them on the same footing as his other tenants. In Ewloe, at least, thelord still exercised the ancient medieval prerogative. It was three members of a family called Holcroft (9) who made a serious attempt to have this situation altered. They by-passed the usual legal procedure of the period, that is, petitioning the Council in the marches of Wales, by opting for a Bill of Complaint to be brought forward at the Court of Requests in London where they thought they would get a just hearing of their case against Edward Stanley, the third Earl of Derby.(10) They sought the right, as was customary in other manors, of digging and taking away any coal that lay within their freehold, citing incidents which had taken place between the Stanleys and themselves. The Stanleys had apparently resorted to force in acquiring some coals what had been dug within the freeholders' land. The Holcrofts were now asserting the existence of unwritten mining codes and that the lord's claim to the coals was unlawful. In his reply the defendant pointed out that the Complainants'

........Bill of Compleynt is uncerten & insufficient in

the lawe to be aniswered unto & the matter theron

conteyind is imagined & contryved .... to put the

said def. to vexacos coste & expens.

He went on to remind the Court that the manor of Ewloe was part and parcel of the lordship of Chester and that his father (in 1535) had been given letters patent to the same (manor) and that accordingly he had papers to prove

that the custom & usage is & tyme wherof the memorie

of and is not to the contrarie hath been that yff eny p'son

or p'sons do digge one Cole within the said manour

having no lycens of the Kings Ma'te or of his fermer

for the tyme being that suche Coles as begotte...

then they had to surrender any profits made; either to the Crown or to its farmer (lessee). Nothing came of the incident and the lord-freeholder relationship seems to have remained unaltered until the Ewloe district had ceased to be the dominant coalmining area in North Wales, that is, about 1575-85. Edward Stanley died in 1573, two years before the expiry of the above mentioned lease, and was described at his death as having been an 'ideot'.(11)

Another incident occurred prior to the Holcroft affair. It concerned John Both referred to earlier. Whether it was an attempt at getting the cleric to surrender his 'customary tenancy' or not must remain speculation, but the events documented could well be so interpreted. Appearing before the Star Chamber, both appealed for the 'most dredde wrytts of subpena' to be served upon some local men for trespass, theft and wanton destruction to his freehold of six acres and coalmines. Only five of the offenders had been detained. They were William Hybberd and his son of the same name and John Hervy (all yeomen); and Richard Maysem and William Hervy (both labourers). They stood accused of having, on the, 20th of June, 1528,

. . unlewfully assembled together with dyv's,

other Riotous p'sons to the nombre of xij p'sons'...

and with force and arm that is to sey with staves

sourds bukkelers and dyv's other wepons aswell

defensyve as invasyve the day and yere above said

into the seyd coll myne have wrongfully entred and

the colles in the same myne growing amountyng

to the value of thre pounds.

From Both's accusations it would appear that the defendants' purpose was more than merely an effort at obtaining cheap coals. There was a deliberate attempt to make the mines unworkable and so to persuade him to relinquish his claim to his fee farm - 'the entent only to dystroy . . . the inheritants of your said subgett.' This they failed to do, but from the events that followed one might reasonably conclude that, from the onset, it had been a well-planned effort to eliminate Both's chances of operating his mine, organised perhaps by a jealous neighbour or even by the lord of the manor himself. Twenty two days later, this time at night, they managed to achieve their goal. On this occasion they

made cast and dygged dyv's trenches Pytts and

Holls in the same coll mynes into which pytts trenches

and holles the water hath so grettly dysended that

your said subgett hath (been) compelled to kepe and

have dyvs p'sons to the nombr of iiij p'sons to convey

carv and rydde the same water....to his grett costs

in the ways and fyndyngs of the same p'sons amountyng

to the Som of £6-13-4d but also to the grett losse

distruceons and decay of his said Coll Myne.

It took the four men forty days to rid the mines of water, conveying it to the surface by means of pails and buckets strapped to their backs . They were paid about 4p a day for their work.(12)

THE LAST HALF of the sixteenth century saw cases of land enclosures clustering the courts of England and Wales due to a rapidly changing agricultural system and also, not to be overlooked, the fact that in 1568 parliament gave landlords the right to seek for minerals under their own lands; although precious metals had to he surrendered to the crown. Such a court case came about in 1581 when John and George Kingesmil complained that some dozen freeholders had intruded upon their premises pretending the same to be their own and 'digging coal mines and wrongfully taking coal within certain enclosures'. Their father, Henry Kingsmill had taken over the lease from the Stanleys in 1575 (for twenty-one years), thus terminating a period of 114 years during which the coalmines had been in the hands of that family. The Kingsmills surrendered the lease before its expiry date. (13) It will become apparent from further information why this came about.

The demand for coal increased rapidly during this period, due mainly to the scarcity of wood. Timber was indiscriminately felled for the rebuilding of dwellings; the county's chief industry, lead, also contributed to the exhaustion of wood supplies by the use of charcoal in the lead smelting process. To combat the shortage new techniques in coalmining had to be found. Problems were encountered as shafts became deeper with the result that costs soared in the effort to rid them of 'choke damp' and flooding. One way of overcoming the financial burden was to form partnerships. This happened in Ewloe in 1594 two men named John Cordrey and William Combe took over the Crown mine for a period of twenty one years at the existing rent of £20-10s. Its location was given as Ewloe Wood.(14) It would seem however that they had backed a 'non- starter', for in the same year it was said that,

By reason wherof of the farme receaveth noe benefitt thereby more

than the gathering of the rente and annsweringe to the same againe.

The reason for this was twofold:

The milles have byn in decaie for manie yeres past (and) noe Coles

(have been) digged here of late because of the great store in other

places most convenent and nerer to the sea and where they are

digged wth less charge.

This last note is most significant and answers the question why the coalmines of the manor of Ewloe declined in importance. One further point is worth observing here. The tenant now claimed the same as their freehold.(15)

THERE WERE COALMINES in other places within a few miles of Ewloe. Whilst touring the country in 1535-6 John Leland observed that there were 'cole pittes a 3. quarters of a mile from Molesdale toune' (16) and no doubt there were pits at Aston and Shotton. In 1547 William Kettel (servant of the Earl of Richmond) complained that he had paid John Duckworthe to open a new coalpit at Great Mancot but the work had not been carried out. Duckworthe maintained that he had acted under the guidance and advice of his 'expert men' - Richard Ledsam, Robert Plethyn and John Ffoxe.(17) It is interesting to note the reference to men being termed 'experts'. No doubt they possessed particular knowledge of mining methods. It was very rare to find coal miners working as a group as early as the reign of Edward VI.(18)

An inquisition post mortem on Thomas Salisbury of Flint held in 1555 revealed that he had coalmines at Hawarden next to Wepre Brook.(19)

Another Salusburie, namely John Salusburie of Rug near Corwen, was also concerned with coal mines in the county in 1569, in conjunction with Edward Thelwall of Plas Coch, Denbighshire, members of the Hanmer family from Maelor Saesneg and others. (20) In other words, Flintshire coalmining during the sixteenth century, was mainly in the hands of the Welsh gentry.

THE LATTER YEARS of Elizabeth's reign saw some Welsh mines

. . .so greatly wrought that they are grown so deep and drowned

with water, as not to be recovered without extreme charges.(21)

Such mines were of the shaft type, an innovation to Flintshire, and only found in the north of the county at Mostyn and its immediate vicinity. There in1603 three pits were producing substantial amounts of coal, about a hundred tons of which were shipped monthly to foreign parts.(22) One shaft of thirty two yards depth was recorded as early as 1580.(23) Mostyn was by now busily becoming engaged in the Irish coal trade as is seen from a letter sent by Gruffydd ap Robert to the mayor of Chester in 1596, notifying him that he had loaded twenty tons of coal from the works at Mostyn onto the William of Chester, for the use of the Lord Deputy ofIreland.(24) This is the earliest reference of this nature known to the present writer. Some figures of Flintshire coal exported to Ireland during Elizabethan times have survived in the Chester Port Books.(25)

1592-3(Christmas to Christmas) . . .182 tons.

1593-4(Michaelmas to Michaelmas). . 180 tons.

1602-3(Michaelmas to Michaelmas). . 802 tons.

A growing trade was also taking place along the North Wales coast, 68 tons being shipped from Mostyn to Beaumaris in 1600.(26) The Ewloe coal trade had been concerned mainly with supplying the needs of the immediate outlying districts. Most of the county still burnt wood, or as was customary in some parts, peat.(27) There is also evidence of coal being taken to Chester by both land and sea routes. In 1494 two men were fined 6s-8d each for bringing carts with iron bound wheels laden with sea coal over the Dee bridge(28) while in 1566 the port authority of Chester saw fit to appoint a couple of Northop men as customs officers at Wepre Pool; so much had trade increased with that city and with IreIand (29) it was said that the brewers, dyers, hatmakers and other tradesmen at this time had long since altered the furnaces and fiery places, and turned the same to the use of burning of sea coal.(30) But the demand for it as a domestic fuel was still confined to places in close proximity to pits. Only the larger towns with easy access to water transportation (such as Chester, Newcastle and London) experienced the burning of sea coal in their hearths. Complaints of the stench from its burning were common at the outset. Some people were extremely sceptical of it. In 1573, for instance, one writer describing the contemporary scene observed that some people

now have many chimnies and yet our tenderlings complain of rheumes, catarrhs...

For as the smoke in those days was supposed to be sufficient hardening for the

timber of the house, so it was reputed as far better medicine to keep the good

man and his, familie from the quack ... where with very few were oft acquainted.

Suggesting perhaps that the extra heat generated by coal was making people more vulnerable to the common cold.(31) An ever increasing demand for coal is revealed in the fact that in 1592 one James Banester petitioned for a money loan of £10 in order that he could supply the 'city of Chester 'in Coles iiij £ better chepe then otherwyse this City can provid'. Unfortunately his application was 'disliked by reason he hath formerly offred and concluded upon other coarse'(32) In the following year however the need must have been greater than the inconvenience, for we find him involved in the delivery of coals at the Watergate within the city; selling it at a somewhat steep price of 6d a barrel.(33)

IT SHOULD BE borne in mind that although there existed a concentration of mines around Ewboe, wood was still a valuable commodity to the community. In 1547, for instance, John Whitbey of Aston assured to Edward Stanley of Hawarden a croft in Ewloe subject to a perpetual yearly rent of six wain-loads of firewood and access to take the same away without hindrance. (34) But coal was increasingly displacing it as the essential fuel.

In 1602 the Council in the marches of Wales was empowered to administer an act of parliament forbidding the use of timber for the making of iron. It was only a matter of time before someone discovered an effective process of making iron and steel or of smelting lead with coal.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1P.R.O. Chester Plea Roll 208/37b; Cheshire Sheaf (Nov.1913),p. 97. I know only one other reference to the term 'scar'in the N.L.W. Chirk MSS for the year1661. There it appears to be equivalent to at least a barrel, if not a ton.

2Black Prince's Register, Part 3. p.308

3B .M.Cal.of MSS relating to Wales ,Part 3, No.25992

4P.R.O. D.K. 36th Rpt, App.II, p. 177

5P.R.O. STA. CHA. 2/5/138

6P.R O. D.K. 37th Rpt, p.263

7P.R.O. D.K. 39th Rpt. p.244.

8Royal Commission, Hist.MSS 6thRpt(1877),p.421 An exemplification of the grant is found in N .L .W.Cal . of Bettisfield MSS, 1647; where the mines are erroneously referred to as being under the seas (probably a misreading of the latin term for coal). Peter Stanley Jnr died in 1 539(seeP.R.O. Lists & Indexes,No.23, Tnq. Post.Mortem Vol. I and chancery S. II, Vol.61, No.96)

9There is a reference to a William Holcroft ,farmer (lessee) (of Holywell parish?) in 1538-9. Recs .Court of Augmentations rel. Wales & Mon. p.96-7. Holcroft was also the name of an eminent Cheshire family.

10P.R,O.REQ.2/25/103.The document is undated but Nef (Rise of the British Coal Industry,Vol.I, p.306) gives the incident as from the reign of Philip & Mary

11B.M..Harl.MS No.2066; P.R.O. Index of lnq. Post Mortem,Vol.2, p.332; P.R.O.Court of Wards,Vol.14,p.79

12P.R.O.STA.CHA.2/5/138; Nef,Vol.2,p.449. John Both died in l542 (Lancs &Chesh.Wills,Rec.Soc.1896, pp.77-.8).His niece Alice held lands in Ewloe in 1551-3

(Early Chancery Proc.Wales, Nos.1309/50-3)

13 Exchequer Proc. Wales ,No.61/4.

14P.R.O. S.P.Dom.(1591.4),p.530.Recs.CourtofAugmentations,Wales, p.398.

15P.R.O. E 310/35/216/1-2

16J. Leland, Itinerary in Wales, ed. L. Touilmin- Smith (1906),p.72. They were probably located at Nant Mawr in the township of Bistre (within the parish of Mold)

17Early Chancery Proc. Con. Wales, Nos .1239/50-2.They' were Ewloe men (ibid. Nos.1309/50-3,1393/27, 1473/7-8

18Trans. Historical Society, 4th Series,Vol. 8 (1915) p.85. I would query the accuracy of a statement made by Taylor, Historic Notices of Flint (1883), p l02, and accepted by Mostyn & Glenn in The Mostyns of Mostyn (1925), to the effect that Richard ap Hywel of Mostyn was escorted by '1600 miners and colliers well equipped for battle' at Bosworth. It is probably an anachronism, arising from a confusion with an incident in the Civil War in 1643 (see Pennant, Tour in Wales, ed.1801). It is important to clarify the point, as coalminers were not organised in such large groups as early as 1485. It is highly unlikely that the coal & leadminers of the whole county numbered more than a hundred at this time.

19F .R .0. Mostyn (Talacre) 160. These mines were contested in the following year.(Early Chancery Proc.Wales,Nos.1473/ 7-8)

20F.R.O.Mostyn (Talacre), p.32

21H .M. S. Rept MSS of Marquis of Salisbury, Vol .14,pp.330-31

22Nef, Vol.1, p.55.

23P.R.O.Gaol File, Wales 4/970/ 3/-

24Chester City R.O. M/MP/8/71

25Nef, Vol. I p.53

26W. Rees, Industry Before the Industrial Revolution, Vol.1 p.74

27G.D.Owen,-Elizabethan Wales (1964), p.46

28R.H.Morris, Chester during the Plantagenet & Tudor Periods, p.275

29A.R.Maddocks,Hist. of Flint.Pt 9(1941).

30G.M. Trevelyan,English Social History, p. 189

31M.C.Borer, People of Tudor England,p.46

32Chester City R.O. A/B/1/238

33ibid. SF/42

34N.L.W. Cal. Coleman Deeds, 1166

Author: Gruffydd, Ken Lloyd 2

Tags

Year = 1971

Month = July

Document = Journal

Landscape = Industrial

Work = Mining

Extra = Pre 1900

Copyright © 2015 The Buckley Society