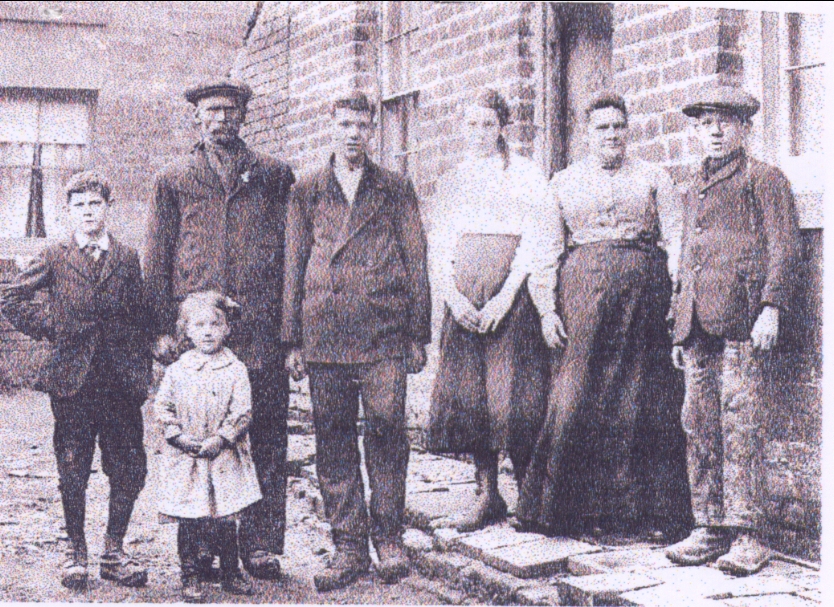

The Morgan family and Benjamin Morgan's story"

Stanley Road, Buckley

1914

BENJAMIN MORGAN HIS STORY. 1904-1984.

When I was born my mother christened me Benjamin, so I guessed she had decided that I was the last, that was in 1904. There were ten of us, 5 sisters and 5 brothers.

As Wendy and Anne Marie haven't seen much of me during your young life, I'll write you this little history. Being at sea for so long was the reason, my sisters were Florrie, Sarah, Minnie and Nellie, my brothers Tom, Joe, Jim and Fred. Father was a miner in North Wales, (Buckley). We were a big family as my mother brought up a granddaughter Alice and adopted a baby as well so there was really a round dozen. We were poor but happy and lively, mother kept us all in good trim. I remember the winter evenings, all of us in the kitchen and the wet working clothes all around the big roaring fire and we'd be pickling onions and red cabbage, or grating down slabs of salt, or making rugs or singing, making toffee and dad mending clogs, mother mending the pit clothes or baking. When we were around the fire after supper ..............On as well, and Prince the dog would chase us all off to bed.

Fred was the best scholar. Some nights he would read to us. We had lots of wonderful books, all Sunday school prizes, Charles Dickens' works. I used to love Oliver Twist & Nicholas Nickleby, The Tale of Two Cities etc. and the Waverly Novels, and Sherlock Holmes.

Dad couldn't read or write but he knew all those stories by heart. When I was about 8 years old a gramophone arrived, with a big horn as big as a modern dustbin. The first record we heard was Schubert's Serenade, and I never forgot it. It's the loveliest piece of music to me; some parts of it were sad and touching and others made me feel warm and happy. At that time Melodeons were all the rage and most of us could knock out a tune and pass the evening away.

My life seemed to start from when I was about 10 years old. Fred had gone to school and mother and me having a duck's egg between us for breakfast. I was recovering from Diphtheria. Anyway the postman knocked the door and told us War had been declared on Germany. There were three letters from Tom, Joe and Jim as they were all working away from home. Tom had joined an Irish Regiment, Joe the Royal Welch Fusiliers and Jim a Guards Regiment. Fred soon left school and went to work in the mines and my sisters went to work in service. I carried on in school until I was 11. We could leave school then, as long as we went to night school, so a job was found for me in the brickyards. In all weathers we tramped about five miles every morning to start work at 7:00am. The job was known as running the bricks. A man would make them by hand on a bench in a wooden mould, and my job was to slide them off and run bare footed down the hot shed and place them carefully on the floor, slide the mould off the brick and run back for the next one. We were paid at the rate of 1 penny per hundred bricks and used to earn about 10/- per week; pocket money was 1d in the shilling from mother. When at night school in the evening, the teacher would have a job to keep us awake we were so tired. This night school lasted until we were 14.

While I was working at the Brickyards my 1st tragedy occurred. Prince our dog was run over. I had taken him to the village to buy a paper to read the war casualties. Prince getting killed was worse to me than all the soldiers lost in France. When I was carrying him home my first love passed me, Annie Edwards. She always seemed to be about when I was at a disadvantage. Annie was a lovely girl, light brown hair and tall with a sweet face and she used to wear a wine velvet frock, I never forgot that. One time I was carrying a bag of flour home from the stores and counting how many lamp posts I could pass without dropping it. Annie stopped me to buy a flag. I hadn't any breath left to speak to her, but I gave her all I had, 3d.

I don't think she even knew I was in love with her. There were six of us lads that worked in the brickyard all about the same age, Arthur Fennah, Flyn Ellis, Charlie Wilcox, Tom Iball, David Pickering. Some days we would be working on the brick machines and the clay would be forced out of a mixer like toothpaste along rollers. One would cut a section off and pass it forward a bit then another would force this piece through six wires, thus you would have five bricks on a board; the others would load the boards on a trolley or biers and rush off and lay them in the sheds to dry. The next day they would be stamped and pressed and reared up in walls before being taken to the kilns to be burned. It was heavy work for boys and after a few months we had muscles like grown men on our arms.

I was smoking before I was 12, but you could get five woodbines for a 1d; still went to Sunday school regular and they organised trips on a Saturday afternoon into the Welsh mountains, but most Saturdays we would be employed by pigeon fanciers. There were no clocks then to time the pigeons. We had certain sections of the country lanes. One lad would get the ring from the pigeon and run so far and hand it over to the next until you reached the club. It was good sport. When the war finished in 1918 I was 14 so I went down the coal mines with my dad. My brothers came out of the army all safe, but Joe had frost-bitten feet and Jim was gassed. Anyway we were all in the mines now. We'd be up at 4:00am and mother with the frying pan on the fire, tomatoes, bacon and sausage.

We all had something to carry - a 14 pound hammer or a pick or a big round-nosed shovel or drills - for Dad. We used to steal apples on the way to work. Fred and me used to see how far we could walk with our eyes shut and try actually to go to sleep going along the road, as there was hardly any traffic of any kind. Once I walked into one of the miners and he turned round and gave me such a smack. I remember his name yet, Simon Jones. It cured me of walking to work asleep. There were lots of mines working in those days - The Mountain, The Elm, Oak and Ash Colliery, all employing about 200 men, but the money was poor. I earned about £2/5/0.

It was very low, about three feet ceiling and the roof was always raining. We were wet through the whole eight hours below. My job was what was known as jigging. There was a pit prop stuck rigid in the floor and roof with a chain around it, the chain fixed to a pulley wheel then a wire rope around the wheel, one end of the wire would be six empty trams or tubs (we called them) on the bottom of the incline or brew; on the other end would be six full trams of coal. I would secure the full trams to the wire and push them over, on rails of course, and then try to steady them with a spar of wood on their journey, but the snag was you couldn't be sure that the six empties were hooked on, with the result, when they wasn't, the wire would come thrashing its way up the hill like a snake and the full trams would run away and smash up at the bottom. It was a wonder we weren't killed and the place pulled on top of us, many a time.

I was in the dark most of the time. I hadn't got the trick of keeping my lamp in, and it was a half mile walk to the nearest safe place to relight it. Fred was driving a pony down the pit; they used to like the apples and sandwiches we brought with us. Our main luxury of the day was when we arrived at the pit top and saw daylight, and on the way home we would collect a cigarette and match we had hidden in a wall or tree on the way to work. We joined a boxing club, and read all the books we could what Jimmy Wilde or Jim Driscoll wrote. Johnny Basham came from our district, the welter weight champ. Summer nights we go for long walks and swimming in the river Alyn. That was the only time we had a bath. There was an old tale amongst miners that baths made your back weak. Fred was only 18 months older than me so we were good pals, also another - George Connah.

It was our ambition to join the Police Force. Joe and Jim were in the Liverpool City Police and we used to go and see them there. George Connah always wanted Jim to arrest someone while we were there. Eventually I did get in the police, but years after. I was so fed up with the mines and wanted to get away, so one morning instead of walking to work I walked to Wrexham 10 miles away and told the recruiting sergeant I was eighteen and joined the Royal Marines. Mother and Dad were upset at the time but laughed about it afterwards. Dad was only concerned about me bringing him a good pair of boots back home. This was in May 1920. 1 went to Manchester to pass some exams so had to stay the night there. I was wandering about the city and stopped an Inspector to ask him where I could get a bed for the night. He turned out to be an uncle of mine. His wife gave it to him for not bringing me to his home, apparently he had other things on his mind. Anyway he fixed me up in a hotel and I never paid anything. The manager just shook hands with me and wished me luck, so I suppose nobody paid.

From Manchester about six of us went London St. Pancras where we were met by a Corporal of marines, who took us to the Admiralty and showed us the sights - Scotland Yard etc. From there we went to Waterloo Station bound for the marine depot at Deal in Kent. There were some fine lads amongst them. I palled up with a lad from Somerset who had been a miner, Tom Summers. We did our commando training, 11 months of it. I never seemed to have my pack off my back, but it was good and healthy, after the wet pits and more money. When my training was completed I joined the 8th battalion in Ireland where there was plenty of trouble. This was in 1921, but when it was all settled in 1922, I came back and got my discharge and a bounty of £20. From there I got a job in a lunatic asylum. I was turned 18 and big and healthy. I was assigned to the refractory ward, all padded cells and all the worst cases. There was many a rough and tumble with them. Amongst us attendants there were a lot of young Irishmen, who just came to save up enough money to get to America. When I was there I wrote to my brother Fred and sister Nellie that it was a good job, and they both came and settled down there, little Alice our niece eventually came as well. George Conch couldn't come. He had lost his arm in a fight. Fred, Nellie and Alice all got married and settled down but I left and joined the Liverpool City Police. I was 21. My brother Joe was there in A division, also Jim in B division. Jim was heavyweight boxing champion of his division. I had an uncle there, a Detective Sergeant, who had the distinction of arresting a murderer. One summer I went to B division. I didn't stay long, only about 9 months. I must have had itchy feet. This time I joined the Royal Navy and went to Portsmouth. After three months training I went on the cruiser YARMOUTH as a stoker. She had 12 boilers and was coal fired. I was only on her a few months as she was due for China trooping. She was taking sailors out to China for the fleet and bringing others back. They would steam her and form the crew. My next three years were spent in the battleships IRON DUKE and BENBOW. They were coal ships and hard work. We were in the home fleet but occasionally went to Spain, most of the time was spent in Scottish waters, Invergorden and Scapa Flow. I used to go to the Highland Games in Inverness and other places. The only way I could get out of those ships was by deserting, so when we returned to Portsmouth for docking, I cleared off to London until they had sailed. I reported to the barracks and did a spell in the cells and the Naval Detention Quarters in the Dockyard, that was quite an experience.

I'll give you a typical day's routine in there. At 5:30am the bell sounded, and the Petty Officers out on the galleries would be shouting out orders, Stand by Your Doors! We had to come out of the cells backwards, so that you wouldn't be in a position to see your mates across the galleries, and signal as if to talk. Walking was not allowed; everything was done at the double. Anyway we'd get the order - 2 paces step back, march right and left turn, double march, then we'd rush away to the workshop, and get one daily task. Mine was making engine room mats. I'd be handed one yard of canvas and a marlin spike, then cut myself off chunks of rope with an axe. This was my thrumbs for the rug, so many strands per hole, so many thrumbs per row, 27 rows completed the engine room mat and it all had to be finished by lights out at 8:00pm. I'd get a few rows in at my breakfast and dinner hour and the remainder in the evening, after 5pm when the day's work was done. Other men would be given tasks according to their rating, such tasks as Jacob's ladders, Ammunition mats, Hammocks, stitching the eyes holes in, ships fenders, or so many pounds of oakum to pick, make coal bags, and many other items. We'd take this back to our cell, then draw a bucket full of water each, strip to the waist and wash, then shave. One of the POs would bring our razors along in a tray, but there was another one behind collecting them back again. We were allowed about one minute. I managed one side of my face, as soon as they were collected you were locked in your cell again, with a bucket of water to scrub your bed boards, a three-legged stool and a little table, after that scrub the deck and wait until the door was unlocked with your bucket and "Jerry". You would hear the pass word Stand by your doors! again, this time to go to the toilets, but you weren't allowed to linger. The PO, shouting Bite it Off, the last man out threatened with all sorts of punishments, put generally run around the parade ground 3 times after you'd taken your bucket and jerry back( I was on the 3rd gallery) and stood by your doors again. We were detailed off for work. It would be 6:30am by now. Incidentally this Stand by Your Doors was a joke throughout the navy. If you walked into a pub some wag would shout out SBYD years afterwards.

From 6:30 until 8:00am you were given all sorts of work throughout the prison, cleaning lavatories, scrubbing chairs and stairs, in the galley, windows, fire equipment etc. At 8:00am back to your cell for breakfast, 1 pint of cocoa, very weak and greasy. A little brown loaf, about 7 ozs and a pat of marg, but you had some task to see you through till 9:00am, then we went to various drills. It may be an hour on a six inch gun, the shell weighed 100lbs, or an hour's rifle drill, but the rifles were old fashioned, long and heavy, running around with them above your head, from that we changed into an hour's physical drill in the Gym. Climbing ropes and the wall bar, box horse jumping, dry land swimming, and complete silence; you'd lose marks for talking or suspected of whispering, and you had to earn so many marks per to day for remission of sentences, or to write a letter on a Sunday afternoon and have a library book on that wonderful day when there was no task or drill, apart for the hour of correct marching before going to church in your best uniform. Another concession was your hammock. After the first 30 days, if you had the required number of marks, but I never qualified, at noon we went to dinner and the task. Some days it would be bran, a basin full, a slice of bread, other days meat and gravy and a slice of bread, on Sundays there was always a piece of steamed dough. Anyway at 1:00pm there was always a nice job going such as scrubbing the dockyard church and the gym, but we did it different to everybody else. We'd have a bucket of water, a plate of sand, 1 scrubber and a cloth. The whistle would blow, and you would sprinkle sand and wet it and start scrubbing, until the whistle went giving you the signal to start wiping. It was known as the scrub out by whistle. That is one reason why I don't like churches or gyms. There was another exercise to keep us busy, it was called "Coaling Ship". There was about five tons of rock in one corner of the drill shed, with barrows and shovels and we would move it from corner to corner until it was time to go to fire drill at 4:00pm until 5:00pm. On Wednesdays and Saturdays it was bath day, also do your own washing. At 5:00pm you were looking forward to the old brown loaf and a pint of tea and of course your rug.

You were allowed two books in your cell, The Stokers Engineering Manual and the Holy Bible; I read both of them. At 8:00pm your task was taken out of your cell whether finished or not. If it wasn't finished you were given a double task the next day and a different diet, mostly biscuits and two pints of water. If the task was damaged you were charged 2/8d, stopped from your pay, (when you started earning some). You couldn't earn any in detention, although there were rumours about halfpenny a day. Therefore, when your time was finished you were in what was known as "Crown Debt" and your liberty was stopped. When you are under stoppage of leave, you answer the bugle calls at all hours, and invariably there is a job waiting for you, such as scrubbing out offices. You can request that whilst in detention. Your allotment can carry on, but that puts you automatically in debt when you come out.

There were about sixty men in at the same time as me and we spent a merry time. I was about 12 stone when I was awarded the punishment, and about 10 when I completed it, also a new pair of boots worn out, bought especially for the occasion. There are other forms of discipline, such as if you refuse to carry out your orders. Then comes solitary confinement. This works out at 72 hours a stretch. I believe the best of them get fed up with it; also with the knowledge that when you return to barracks, the Commodore can and may award you with another 90 days of the best.

I volunteered for foreign service as soon as I was free, and joined the destroyer STUART and sailed the Mediterranean for two and a half years. The fleet's base was Malta, a lovely place for swimming and enjoying yourself. There were cruises to different countries, Spain, Greece, Italy, France, Yugoslavia, Egypt etc. It was all very interesting. After two and half years I came home and had a month's leave, and went back for another tour, this time on the cruiser COVENTRY. It was the flag ship. I spent most of my time in the engine room and on refrigeration machinery. I did a lot of reading and studying and decided to go in for promotion. I passed the exam for Leading Hand and was eventually 'Made' towards the end of that commission after eight year's service.

Mother died while I was on that ship, also brother Tom who was killed in the mines (Llay Main Colliery, Wrexham). I had still 4 years to service. I volunteered for South Africa in the cruiser AMPHION. I got it as I was now First Class for conduct. Our station was Simonstown 20 miles from the Cape of Good Hope. I spent nearly three years there. My job was on the dynamos, and then in charge of the catapult, as we carried three planes. After that commission, the ship was transferred to the Royal Australian Navy. I was sent to training school for Petty Officers. I was made Petty Officer and was waiting to proceed to China to the Gunboats. We knew war was looming up and we wouldn't be released in anycase, so I signed my name for another 10 years, to complete time for a pension. In August 1939 I was in Portsmouth Barracks with no ship and expecting mobilisation. At 3:00am on the 3rd of August we were roused out and boarded a train with our bags and hammocks, just a thousand of us, boarded a ship for Dieppe, France. We went straight across France where a cruiser was waiting at Marseilles to take us to Alexandria, where we were commissioned in the third Minesweeping Flotilla (9 ships). We arrived in Alexandria on a Sunday night and commenced straight away to coal ship, provision water, ammunition etc: I went to one called HMS SUTTON, 800 tons twin screws and carried on sweeping the channel for mines until war was declared on September 3rd 1939. It was a Sunday morning; we were served with a bottle of beer for dinner that day, and hoisted the empties up the mast.

We sailed for England in December, short of bread all the way, 3000 miles, after a few stops for coal at Malta and Gibraltar and of all places Grimsby. 1st of January 1940, I visited as many a pub as I could that night for next morning we were going to the Tyne. To start sweeping down the coast as far as Harwich. The mines were thick and hundreds of ships were sunk and most of the tankers set on fire. It was known as E Boat Alley. In July (2nd) 1940 I met Molly Trevor. It was love at first glimpse, never mind sight. She was married but what did that matter. She got divorced and we were married on May 27th 1941. I was waiting for her in the Old Kings Head with my best man, when they announced the sinking of Germany's biggest battleship the Bismark, so I had an extra pint. I had been blown up just previous by a mine off Imingham but we didn't sink, but it meant three months in dock. Anyway we got married and Molly nearly got locked up that night for pointing her torch to the sky.

Footnote. Ben served through out the rest of the war in Trawlers on minesweeping duties, leaving the navy in 1946 after 21 years service. He then joined the Merchant service and worked on tankers until 1970. He then retired ashore, and worked in the Hepburn and Walker shipyards in Newcastle on the fitting out basins, as a mooring officer. He finally retired and came to live with his brother Jim in Wrexham for a little while, before moving down south again, where he remained until his death in 1984.

Author: Morgan, Benjamin

Tags

Year = 1914

Building = Domestic

Gender = Mixed

Landscape = Domestic

People = Family

Extra = Fashion

Extra = Formal Portrait

Extra = 1910s

Copyright © 2015 The Buckley Society